Researchers at the University of California San Diego have made significant strides in understanding the synchronization of oscillators within the intestine, revealing how they facilitate the digestive process. This groundbreaking research, published in Physical Review Letters, explains the mathematical principles that enable these oscillators to lock onto one another, creating a staircase effect that aids in digestion.

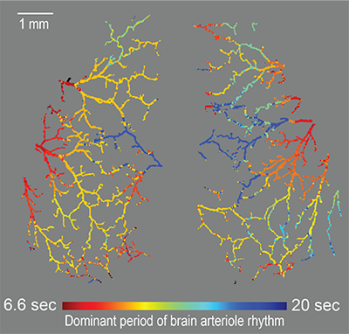

Synchronization is a common phenomenon in nature, evident in various biological systems, from the synchronized flashing of fireflies to the coordinated movement of fish in schools. In the human body, the vasculature of the brain exhibits oscillatory behavior, where blood vessels expand and contract in response to neural activity to regulate blood flow, oxygen, and nutrients. However, the underlying mechanisms of this synchronization remain poorly understood.

To explore these mechanisms, Kleinfeld and his team focused on the gut, where they observed that oscillators operating at similar frequencies could lock onto one another in succession. This phenomenon creates a staircase effect in the digestive tract. According to Kleinfeld, applying an external stimulus to a neuron causes the entire vascular system to synchronize at a uniform frequency. In situations where two neuron sets are stimulated at different frequencies, some arterioles synchronize at one frequency while others at another, resulting in the staircase effect.

To investigate this further, Kleinfeld collaborated with Massimo Vergassola, a professor of physics specializing in the physics of living systems, along with graduate student Marie Sellier-Prono and researcher Massimo Cencini from the Institute for Complex Systems. They utilized a classical model of coupled oscillators adapted to the digestive system. The gut naturally oscillates due to peristalsis, which involves the contraction and relaxation of muscles in the digestive tract, allowing for a simplified model compared to the complex network of blood vessels in the brain.

The gut”s unidirectional flow ensures that frequencies shift in a gradient from higher to lower, facilitating the movement of food through the digestive tract. “Coupled oscillators communicate with each other, and each segment of the intestine acts as an oscillator that interacts with adjacent sections,” explained Vergassola.

Previous studies on intestinal oscillators had confirmed the presence of a staircase effect, where similar frequencies synchronize with neighboring oscillators, promoting rhythmic food movement. However, the specific characteristics of this staircase effect, including the height of the rises and the conditions under which it occurs, had not been thoroughly defined until now. This new mathematical framework answers essential questions about the mechanisms of food movement and churning in the digestive system.

The researchers hope that their findings will pave the way for further investigation into gastrointestinal motility disorders, which are related to peristalsis and can lead to various health issues. “While earlier mathematical models provided approximate solutions, they did not account for the critical breaks in the staircase effect. This discovery is pivotal,” noted Kleinfeld.

Having addressed the oscillatory dynamics of the gut, the research team plans to return to studying the brain”s intricate vascular system, which presents a far more complex network than that of the gut. While the gastrointestinal tract”s staircase effect occurs in a straightforward manner, the brain”s vascular pathways feature multiple directions and varying lengths, complicating the synchronization process. “The brain”s complexity far exceeds that of the gut, but this is the essence of scientific inquiry,” Kleinfeld remarked. “One question leads to another, and addressing each problem deepens our understanding of the original inquiry.”

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health BRAIN Initiative.