In a remarkable technological achievement, a small piece of metal engineered in Australia has significantly enhanced the imaging capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope, which is stationed approximately one million miles from Earth. This innovation was crucial in refining the telescope”s vision, which had initially faced challenges.

After the successful launch of NASA”s 10 billion-dollar James Webb Space Telescope in December 2021, the anticipation grew as six months later, the telescope unveiled its first images of some of the most distant galaxies known. However, the work for the Australian team was just beginning.

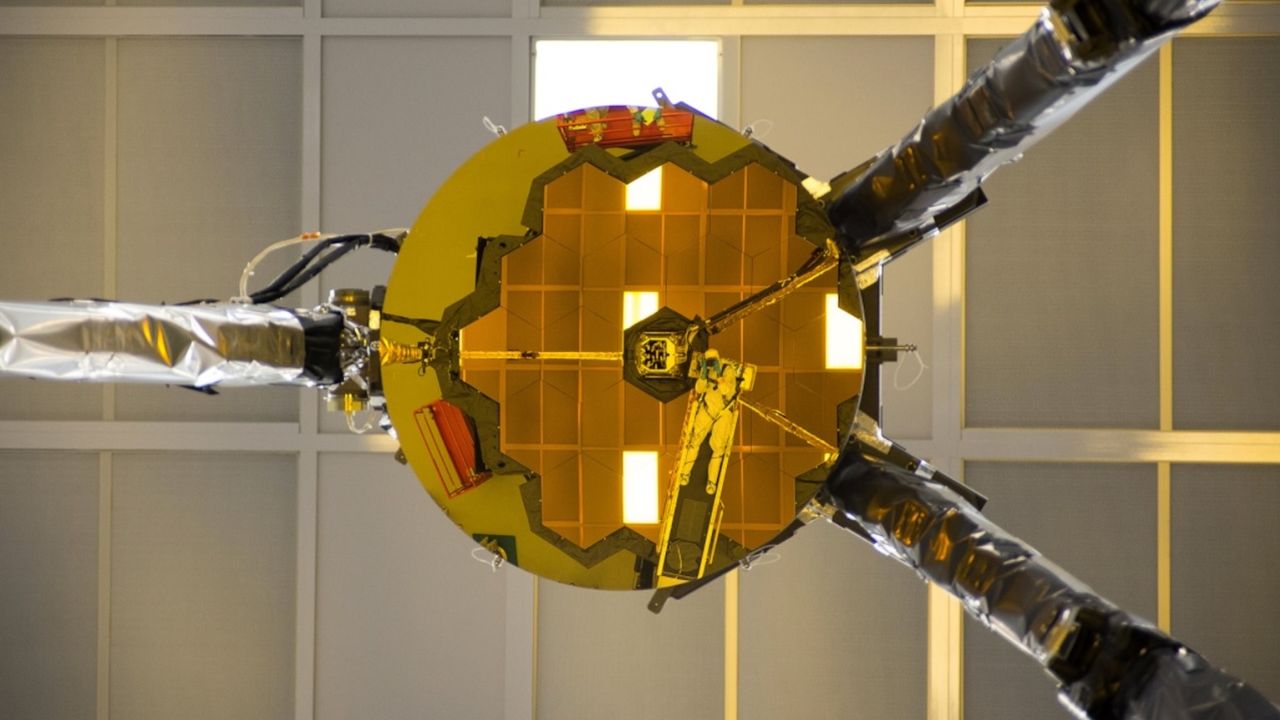

Utilizing a high-resolution mode named the aperture masking interferometer, or AMI, the team aimed to improve the telescope”s resolution. This finely crafted metal component was inserted into one of Webb”s cameras, allowing for a more precise analysis of its images. Recently, findings from this effort have been published in two papers on the open-access archive arXiv, showcasing its inaugural observations of various celestial bodies, including stars, planets, moons, and even jets from black holes.

Unlike the Hubble Space Telescope, which orbits a few hundred miles above Earth and can be serviced by astronauts, the Webb telescope”s position makes direct intervention impossible. This limitation necessitated a solution that could diagnose and correct any optical distortions remotely. AMI was specifically designed by astronomer Peter Tuthill to identify and measure any blurring in Webb”s images, as even minute distortions in its primary mirrors could significantly impact scientific observations.

Through testing, it became evident that at extremely fine resolutions, a problem known as electronic crosstalk was causing blurriness in images. This issue arose when brighter pixels interfered with their darker neighbors, complicating the detection of faint celestial bodies. The team quickly realized that the impact of this distortion was far more significant than anticipated, particularly when observing distant planets.

In response, a collaborative effort led by Louis Desdoigts, a PhD student at the University of Sydney, employed AMI to analyze and rectify both optical and electronic distortions. By developing a computer model to simulate AMI”s optical physics and integrating it with a machine learning framework, they successfully restored clarity to the captured data without altering the telescope”s physical operations.

This breakthrough allowed for clearer observations of specific celestial objects, including the star HD 206893, which hosts a faint planet and the reddest known brown dwarf. Before this correction, these features were virtually undetectable. The successful application of AMI has opened new avenues for discovering unknown planets and enhancing the resolution of images produced by the telescope.

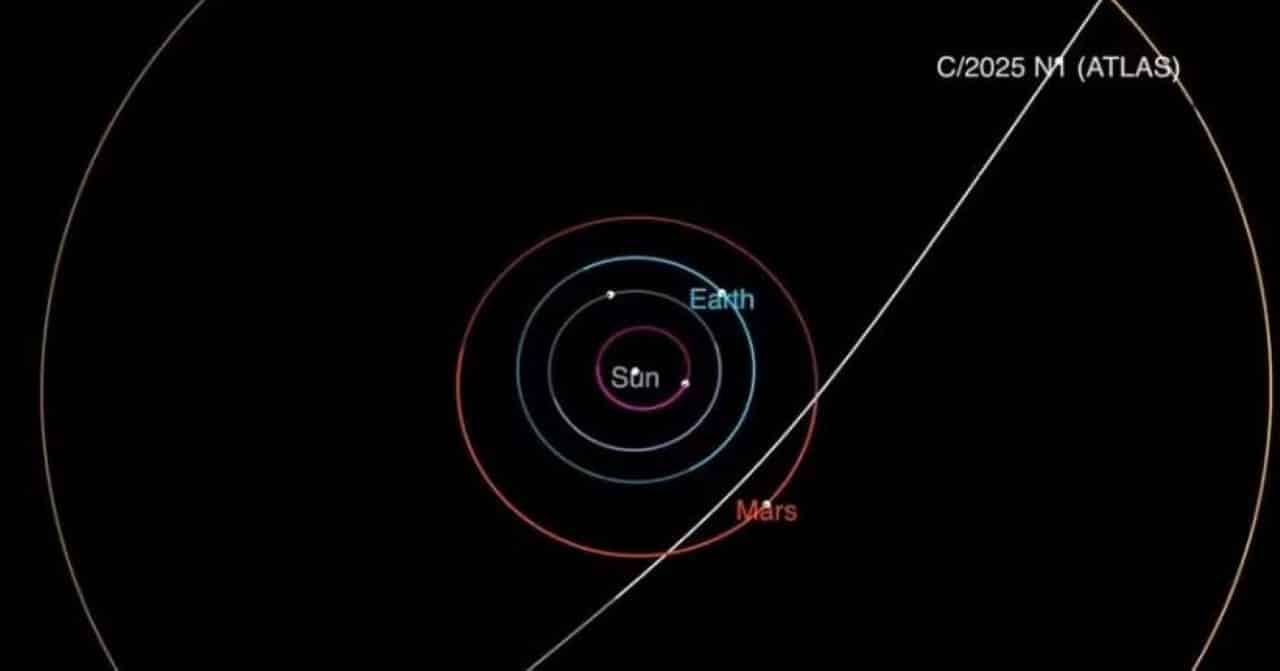

Complementing this work, another study by PhD student Max Charles expanded the capabilities of AMI to capture more complex images. By revisiting previously studied targets, the researchers were able to achieve unprecedented detail, including the volcanic activity on Jupiter”s moon Io and the jets emanating from the black hole in galaxy NGC 1068. AMI”s ability to resolve intricate features, such as a dust ribbon around the stars in the WR 137 system, has further validated theoretical models.

The advancements made with AMI serve as a prototype for future optical systems on the Webb telescope and its successor, the Roman space telescope. This research underscores the potential for achieving highly precise calibrations, which are essential for the discovery of Earth-like planets in distant galaxies.