A team of astronomers has identified a white dwarf star, approximately 3 billion years old, that is actively drawing in material from its previous planetary system. This remarkable finding, reported in a paper published on October 22 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, prompts a reevaluation of established theories regarding the evolution of stellar remnants.

As the Sun approaches the end of its life, expected in about 5 billion years, it will transition into the Red Giant Branch phase, expanding and potentially engulfing Mercury, Venus, and possibly Earth. This phase will be followed by a gravitational collapse, leading to the formation of a white dwarf. However, the discovery of LSPM J0207+3331, located 145 light-years away in the constellation Triangulum, reveals that some white dwarfs may continue to interact dynamically with remnants of their planetary systems long after their formation.

The research team, which includes members from the Université de Montréal, the Centre de Recherche en Astrophysique du Québec, and the Carnegie Institution for Science, utilized the High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES) at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. They detected a variety of chemical elements typically associated with rocky bodies, including sodium, magnesium, aluminum, silicon, calcium, titanium, chromium, manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, copper, and strontium.

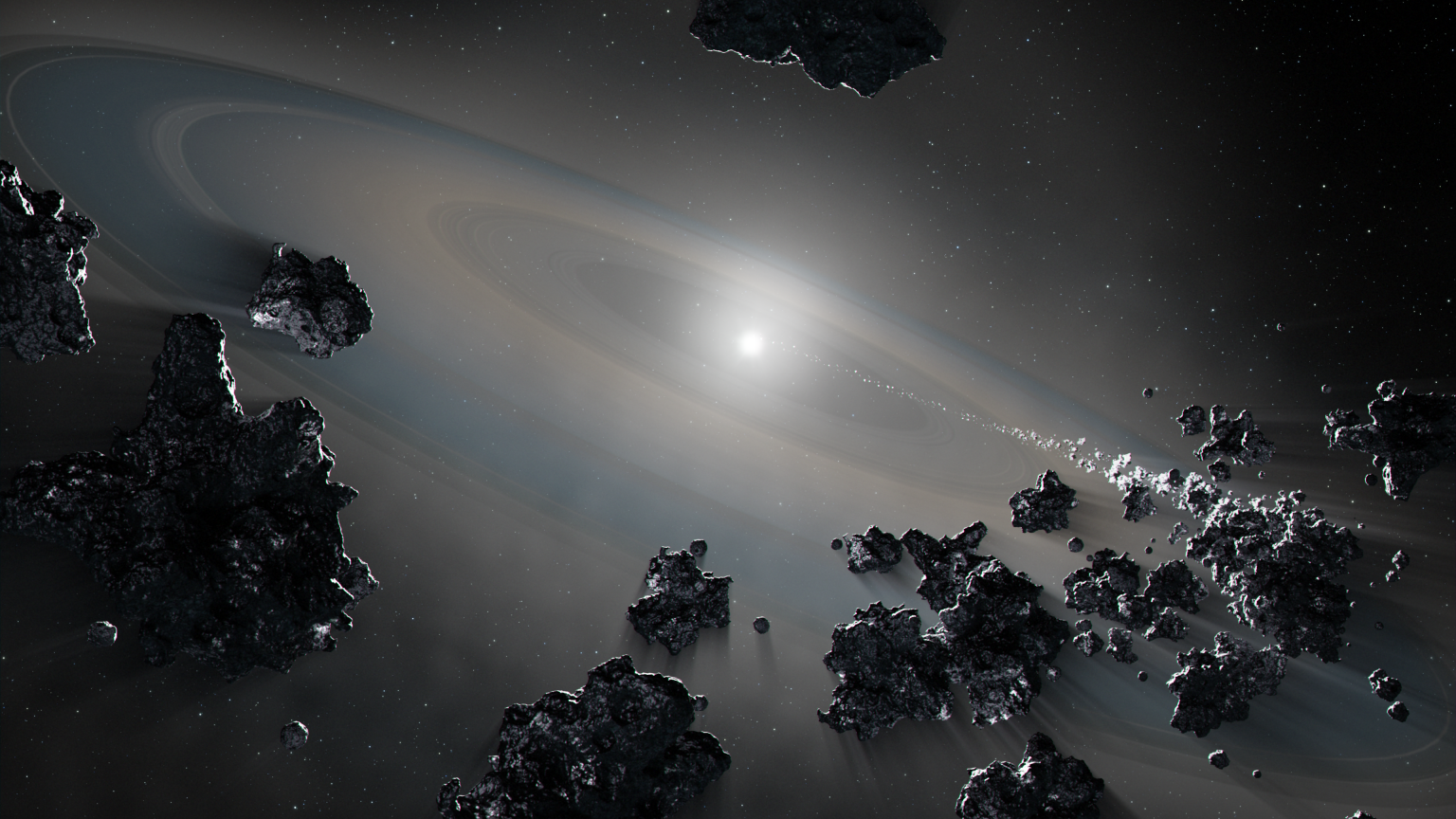

According to the analysis, these minerals likely originated from a differentiated rocky body, with a diameter of at least 200 kilometers, that was disintegrated by the gravitational forces of the white dwarf. The resulting debris disk surrounding this ancient star is the oldest and most metal-rich observed around a hydrogen-rich white dwarf to date.

Lead author Érika Le Bourdais from the iREX Institute stated, “This discovery challenges our understanding of planetary system evolution. Ongoing accretion at this stage suggests white dwarfs may also retain planetary remnants still undergoing dynamical changes.”

The presence of heavy elements indicates that LSPM J0207+3331 still possesses a planetary system that has experienced significant disturbances, potentially due to interactions with a passing star or rogue planet. The researchers hypothesize that the gravitational perturbation likely occurred within the last few million years, causing the rocky body to spiral inward toward the star.

The findings raise intriguing questions about the future of our own Solar System. Co-investigator John Debes from the Space Telescope Science Institute noted that the next steps involve investigating what may have disrupted the system, which might include detecting a Jupiter-sized planet still orbiting LSPM J0207+3331.

While directly observing such a planet could prove challenging, measurements of its gravitational influence may be achievable. The European Space Agency”s Gaia Observatory could offer insights into the gravitational dynamics, while infrared observations from NASA”s James Webb Space Telescope could assist in searching for outer planets within this unique system.

This discovery not only reshapes our understanding of stellar evolution but also provides a glimpse into the eventual fate of our Solar System.