If you have ever pondered the reason behind the giraffe”s remarkably long neck, the explanation is often attributed to their ability to reach lush leaves high in African acacia trees. This unique adaptation allows giraffes to access a food source that is not available to smaller herbivores, which tend to forage closer to the ground. This dietary advantage enables giraffes to reproduce year-round and withstand drought conditions more effectively than their shorter counterparts.

However, the giraffe”s elongated neck imposes a significant physiological challenge. The heart must generate sufficient pressure to pump blood over two meters up to the head, resulting in a blood pressure that typically exceeds 200 mm Hg—more than double that of most mammals. Consequently, the energy required by a resting giraffe”s heart surpasses the total energy consumption of a resting human and exceeds that of any mammal of similar size.

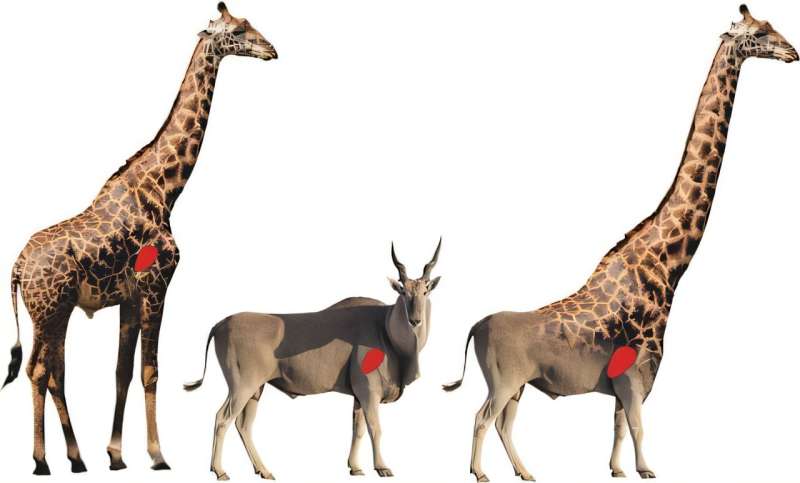

A new study, published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, highlights an intriguing discovery regarding how giraffes manage this energetic burden: their long legs play a crucial role. Researchers conducted an analysis of the energy costs associated with blood circulation in a typical adult giraffe and compared it to an imagined creature with a shorter leg length but a similarly extended neck, referred to as an “elaffe,” a hybrid of the body of a common African eland and a giraffe”s neck.

The findings revealed that this hypothetical elaffe would utilize a staggering 21% of its total energy on heart function, in contrast to 16% for giraffes and merely 6.7% for humans. By virtue of their long legs, giraffes effectively reduce the energy expenditure required for blood circulation by a net 5%, which translates into an annual energy savings equivalent to over 1.5 tons of food. Such an advantage could be critical for survival in the competitive environment of the African savannah.

According to zoologist Graham Mitchell, in his book How Giraffes Work, the ancestors of giraffes developed long legs prior to their necks. This evolutionary progression is beneficial from an energy perspective, as longer legs ease the heart”s workload, while longer necks increase it. However, this adaptation presents its own set of challenges. Giraffes find it cumbersome to drink water, as they must spread their forelegs, making them vulnerable to predators and often leaving water sources without hydrating.

The study also raises questions about the limits of neck length and the associated energy costs. For instance, the Giraffatitan, a sauropod dinosaur that stood 13 meters tall, would have required an impractical blood pressure of about 770 mm Hg to circulate blood to its head. Such demands would have rendered it impossible for any terrestrial animal to achieve heights exceeding that of a full-grown giraffe without experiencing severe physiological consequences.

This research sheds light on the complex interplay between anatomy and energy efficiency in giraffes, illustrating how their unique adaptations have evolved to support their survival in a challenging ecosystem.