On November 4, 1922, an archaeological team led by Howard Carter made a groundbreaking discovery in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt. During the excavation, Egyptian workers uncovered a staircase leading down to the tomb of King Tutankhamun, a pharaoh who had died over 3,200 years prior as a teenager.

The team was clearing sand near the tomb of Ramesses VI when they found the first hints of the steps, located approximately 13 feet (4 meters) below the surface. Some accounts suggest that a water boy named Hussein Abd el-Rassul may have initially spotted the steps. Recognizing the significance of their find, the crew worked tirelessly until they reached the 12th step, where they discovered a small plaster-covered doorway.

In his diary, Carter noted that the door bore a seal from the Royal Necropolis, featuring the god Anubis depicted as a king over nine defeated foes. “Here before us was sufficient evidence to show that it really was an entrance to a tomb, and by the seals, to all outward appearances that it was intact,” he wrote on November 5.

Upon further exploration, the team found that the entryway had been filled with rubble, likely placed there by priests to conceal the tomb, reinforcing their belief that it had remained untouched. Over the following weeks, the team excavated the steps and doorway, eventually uncovering a seal with the cartouche of King Tutankhamun on November 24.

Despite the discovery, uncertainty lingered regarding who was buried inside. The rubble presented a confusing mix of pottery shards and broken boxes linked to various ancient Egyptian rulers, including Akhenaten, Tut”s father. On November 25, Carter and his team opened the first door to the tomb, and the following day, they found a second door, through which they cautiously peered.

Attending the unveiling were Lord Carnarvon, who financed the excavation, along with his daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert and engineer Arthur Callender. All were anxious to witness the treasures contained within. “It was sometime before one could see; the hot air escaping caused the candle to flicker. But as soon as one”s eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light, the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another,” Carter recounted.

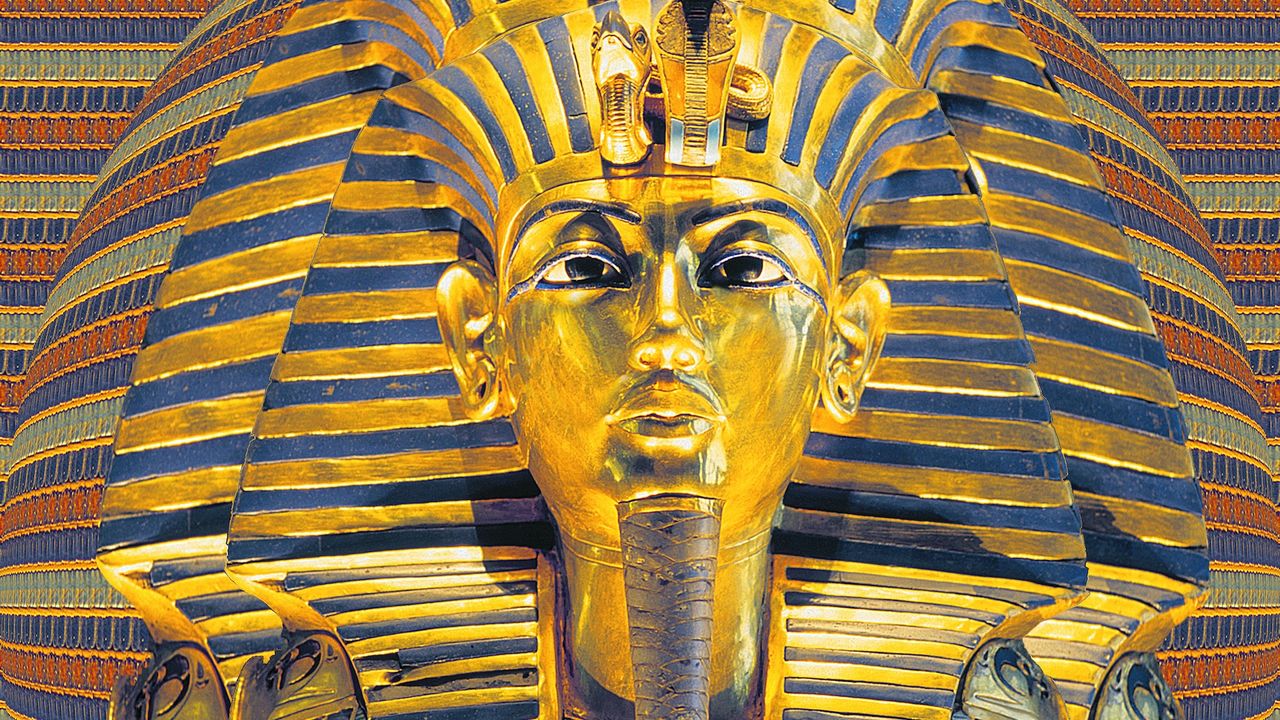

The tomb of King Tutankhamun became renowned as the first unlooted pharaoh”s tomb found in modern times, filled with an array of treasures. Among the most iconic artifacts was his elaborate death mask, weighing 22 pounds (10 kilograms) and crafted from solid gold, adorned with semiprecious stones. Additionally, Tutankhamun was buried with board games, multiple beds, and even a mannequin intended for trying on outfits in the afterlife.

King Tutankhamun”s remains were interred in three nested coffins, two made from gilded wood and the innermost, smaller coffin constructed from solid gold. His body was treated with oil that darkened it before the mummification process. Shortly after the tomb”s discovery, Lord Carnarvon died due to an infected mosquito bite, leading to widespread media speculation about a so-called mummy”s curse.

In 1923, Pearson”s Magazine published a fictional tale titled “The Tomb of the Bird,” which included a storyline about Carter”s deceased canary found in the mouth of a cobra shortly after the tomb”s unveiling. These narratives, combined with a few other coincidental events, fueled the belief in a curse that supposedly afflicted those who disturbed a pharaoh”s resting place. However, a study conducted in 2002 indicated that the 25 Westerners who had entered the tomb lived approximately as long as expected for their time, debunking the myth of the curse.