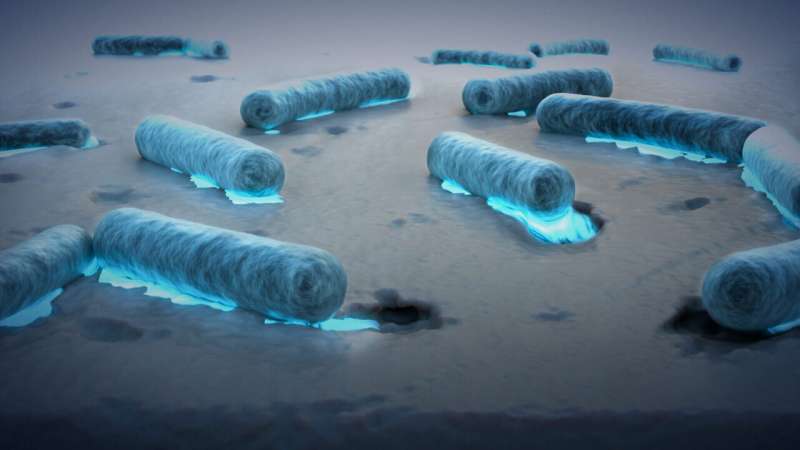

Deep within the oceans, marine bacteria possess enzymes capable of breaking down plastic, showcasing their evolutionary adaptation influenced by human waste. Researchers from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology have conducted a global survey revealing that these microorganisms, which act as natural recyclers, are not only prevalent but also genetically equipped to metabolize polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a common polymer found in products ranging from soda bottles to textiles.

The study, published in the ISME Journal, highlights a significant discovery: a structural feature on the PET hydrolase enzyme, referred to as the M5 motif, which indicates the enzyme”s capability to degrade PET plastic. “The M5 motif serves as a fingerprint, suggesting when a PETase is likely functional and can effectively break down PET,” explained Carlos Duarte, a marine ecologist and co-leader of the research. “This finding sheds light on how these enzymes have evolved from other hydrocarbon-degrading enzymes.” In carbon-scarce ocean environments, these microbes appear to have adapted their enzymes to utilize plastic, a new carbon source introduced by humans.

Previously, PET was thought to be nearly indestructible in natural settings. However, a breakthrough occurred in 2016 when scientists identified a bacterium in a Japanese recycling facility that thrived on plastic waste and produced PETase, an enzyme capable of decomposing plastic into its basic components. Despite this, it remained uncertain whether similar enzymes had emerged in marine environments.

Through a combination of artificial intelligence-based structural modeling, extensive genetic analysis, and laboratory experiments, Duarte and his team demonstrated that the presence of the M5 motif distinguishes actual PET degraders from similar enzymes. Their laboratory tests confirmed that marine bacteria with the complete M5 motif could effectively break down PET. Gene activity measurements revealed that M5-PETase genes are actively expressed in ocean waters, particularly in areas with significant plastic pollution.

The research team analyzed over 400 ocean samples from various locations, discovering functional M5 motifs in nearly 80% of the tested waters, ranging from plastic-laden surface gyres to nutrient-depleted depths two kilometers below the surface. According to Intikhab Alam, a senior bioinformatics researcher and co-leader, the ability to consume synthetic carbon may offer these bacteria a vital survival advantage in such extreme environments.

The emergence of these enzymes represents an early microbial reaction to the extensive plastic pollution created by humanity. Duarte cautions that the natural mechanisms for cleaning up this waste are insufficient to mitigate the damage already done to marine ecosystems. “By the time plastics reach the deep sea, the threats to marine life and human health have already been established,” he stated.

On land, however, this discovery has the potential to accelerate the design of industrial enzymes aimed at closed-loop recycling systems. “The diverse range of PET-degrading enzymes that have evolved in deep-sea environments can serve as models for optimization in laboratory settings, ultimately facilitating more efficient plastic degradation in waste treatment facilities and even at home,” Duarte added. The M5 motif now provides a foundational blueprint, highlighting essential structural modifications that could enhance enzyme function in real-world scenarios, beyond mere laboratory conditions. If scientists can leverage these adaptations, they may find unconventional partners in their quest to address plastic pollution: bacteria that already convert waste into sustenance.