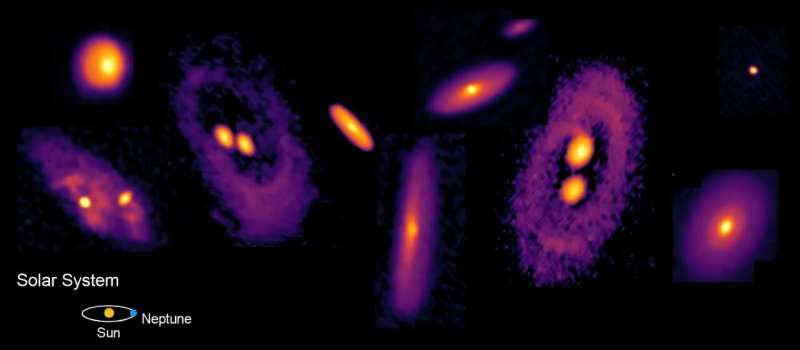

In a significant advancement in the quest to understand planet formation, researchers utilizing the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have discovered that planets may begin to take shape much earlier than previously thought. This new study involved imaging 16 protoplanetary disks surrounding young Class 0 and Class I protostars, indicating that the process of planet formation could commence while the stars are still in their formative stages.

The findings of this research are set to appear in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics in an article titled “FAUST. XXVIII. High-Resolution ALMA Observations of Class 0/I Disks: Structure, Optical Depths, and Temperatures.” The study is currently available on the arXiv preprint server and is led by Dr. Maria Jose Maureira Pinochet, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics.

The ongoing FAUST project, which stands for Fifty AU Study, aims to examine the envelope and disk systems of solar-like Class 0 and I protostars at approximately 50 astronomical units. Historically, astronomers believed that the formation of planets occurred after the star had fully formed. However, this new evidence supports the idea that planet formation may begin during the embedded protostellar phases.

The embedded stage refers to when young protostars are shrouded in dense clouds of gas and dust. During this critical phase, they are actively accumulating mass. Observing protostellar disks is challenging due to the thick layers of material that obscure visibility. Nonetheless, ALMA has proven to be an effective tool for this purpose.

By analyzing the 16 Class 0 and Class I protostellar systems, the researchers found that these early disks serve as a crucial link between the collapsing cloud of gas and the subsequent stages of planet formation. “These baby disks bridge the gap between the collapsing cloud and the later planet-forming stages,” stated Paola Caselli, Director at the Center for Astrochemistry at MPE and a co-author of the study. “They provide the missing link for understanding how stars and planets emerge together.”

Despite improvements in observational resolution, there remains a pressing need for further studies of these young systems. A primary objective is to identify when substructures in disks, similar to those seen in Class II disks, begin to form in Class 0 and Class I disks. Class II disks are characterized by their thickness but lack the heavy embedding of their younger counterparts.

To date, astronomers have studied nearly 60 Class 0 and Class I disks, yet only five have exhibited clear substructures, all of which were found in Class I disks. “These results suggest either that planet formation begins during the Class I stage or that many younger disks remain too optically thick at approximately 1 mm, preventing the clear detection of substructures,” the researchers explained.

The team identified one confirmed substructure, previously noted in other studies, as well as a potential second substructure. This indicates that additional hidden structures may exist, obscured from detection. “These results support the idea that annular substructures can emerge as early as the Class 0 stage but are often concealed by optically thick emissions,” the authors noted.

Furthermore, their research indicates that these young disks are approximately ten times brighter than more evolved disks, a characteristic attributed to their mass and thickness. “Our results show that self-gravity and accretion heating play a major role in shaping the earliest disks,” remarked Hauyu Baobab Liu from the Department of Physics at the National Sun Yat-sen University in Taiwan. “They influence both the available mass for planet formation and the chemistry that leads to complex molecules.”

As researchers continue to unravel the mysteries of planet formation, facilities like ALMA and other upcoming instruments, including the Square Kilometer Array and the Next Generation Very Large Array (ngVLA), will be vital in observing these obscured disks at longer wavelengths. “Observations at longer wavelengths are necessary to overcome these issues. Future observations with SKAO and ngVLA, along with more sensitive observations with ALMA, will be key for advancing our understanding of early disk and planet formation and evolution,” the authors concluded.