Nicté Yasmín Luna Medina, a mother, feminist, and science communicator affiliated with the Institute of Renewable Energies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), has shed light on a groundbreaking energy solution. Located in the heart of the Mojave Desert in the United States, a solar tower shines brightly at its summit, surrounded by numerous mirrors that create a mandala-like pattern on the ground. This impressive structure is not a weapon of war, as the fictional Aureliano from Gabriel García Márquez”s novel might think, but a significant technological advancement designed to generate electricity by concentrating solar energy.

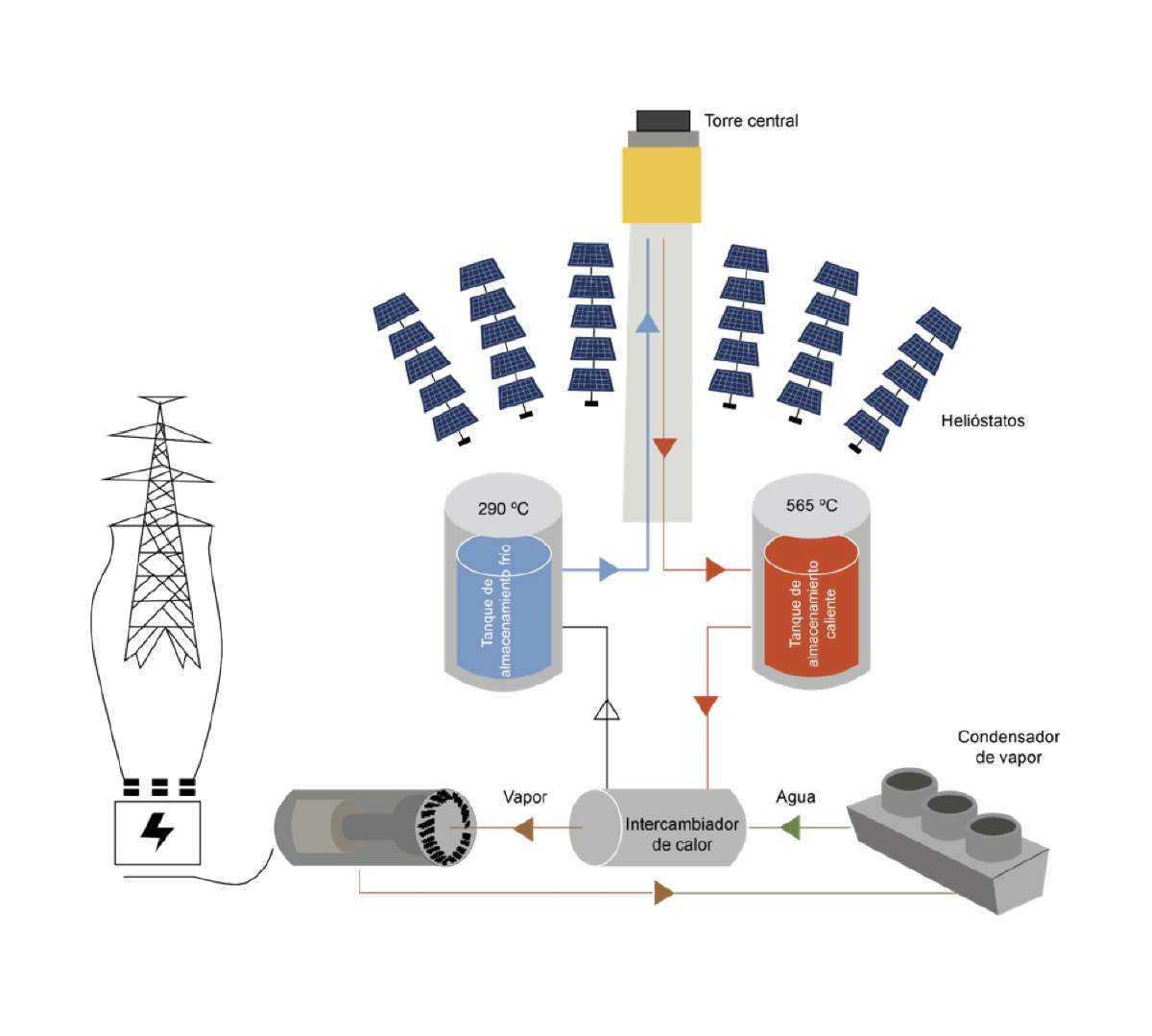

This technology, known as a solar thermal tower, utilizes mirrors called heliostats. These heliostats reflect solar radiation towards a receiver located at the top of the central tower. They are equipped with control mechanisms that allow them to track the sun”s movement throughout the day. The receiver, composed of numerous tubes, transfers the captured heat to a working fluid, which may be water or molten salts. When water is used as the fluid, steam is produced directly in the receiver. In contrast, molten salts are heated in the receiver and then transfer their heat to water in a heat exchanger, converting it to steam. This steam drives a turbine connected to an electric generator, thus producing electricity.

Significantly, these solar thermal plants are equipped with storage systems to retain the heated fluid, especially when molten salts are utilized. This capability allows for operation during nighttime or cloudy days, unlike steam, which can only be stored for brief periods. To grasp the enormity of this achievement, consider the amount of solar energy that naturally reaches Earth. On a clear day at noon, solar radiation hitting the planet”s surface is roughly equivalent to 1 kilowatt per square meter, akin to having ten 100-watt light bulbs illuminated over a square meter of land. A central tower can concentrate solar energy up to 600 times, meaning the receiver can potentially receive up to 600 kilowatts of solar power, operating at temperatures between 250°C and 1000°C, which are necessary for running a steam turbine and generating electricity.

However, merely concentrating light is not enough; the design of the tower and the arrangement of the mirrors are crucial for maximizing solar radiation capture. The tower”s height must be sufficient for the heliostats to “see” the receiver directly, ensuring the angle between the mirror, the sun, and the receiver is optimal for reflecting the maximum amount of light. Additionally, the positioning of each heliostat should prevent shading or blocking from one another to enhance radiation reflection. Ideally, the maximum distance between the tower and the heliostats should not exceed one kilometer.

The technological development of solar thermal towers has demanded research across various fields, including the types of fluids used for steam production, storage systems, and overall system design. The initial advancements in this area began in the early 20th century, prompted by the oil crisis of the time. Early experiments utilized water as a working fluid, limiting the steam temperature to around 250 degrees Celsius and impacting system efficiency. To improve this, engineers began exploring various fluid mixtures. In 1902, H. E. Willsie and J. Boyle Jr. first experimented with water mixed with ammonia, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide to elevate steam temperatures.

Another notable contribution came from American inventor and solar energy advocate Frank Shuman, who in 1908 developed the first recorded solar thermal energy storage system, crucial for extending electricity production hours during the night or on cloudy days. In 1949, N.V. Lenitski in Moscow proposed a system using flat mirrors to reflect sunlight onto a fixed raised boiler. By 1957, Vicky Baum introduced the first design of a central tower featuring 1,293 mirrors, each measuring 3 by 5 meters, arranged in 23 trains moving on concentric rails around a 40-meter-high boiler.

In 1965, Professor Giovanni Francia from the University of Genoa in Italy conducted further tests at a pilot plant in St. Ilario-Nervi, consisting of 270 circular heliostats, each 1.1 meters in diameter, generating steam at 500°C. The lessons learned from these prototypes laid the groundwork for integrating these solar plants into the electrical grid. In 1996, the Solar Two plant, the first demonstration facility to inject electricity into the U.S. grid, began operations in the Mojave Desert. Unlike its predecessor Solar One, which used oil or water, Solar Two utilized molten nitrate salts heated to 650 degrees Celsius, featuring 1,926 heliostats with a capacity to generate up to 10 megawatts of electricity.

With the success of Solar Two, the technology transitioned from experimental to a viable electrical generation option, leading to the establishment of commercial solar thermal plants. In 2006, the world”s first solar thermal tower, PS10, commenced operation in Sanlúcar la Mayor, Spain, consisting of 624 heliostats and a 114-meter-high tower with an output capacity of 11 megawatts. This facility spans 60 hectares and utilizes water as a working fluid, limiting its operational steam temperature to 250 degrees Celsius.

On the other hand, the Gemasolar plant, inaugurated in 2011 in Seville, marked the first commercial-scale solar thermal facility with thermal energy storage capability using molten salts. Covering an area of 185 hectares, it comprises 2,650 heliostats, each with an area of 120 square meters, arranged in concentric rings around a 140-meter tower. This plant produces 19.9 megawatts of power and features a thermal energy storage capacity of 15 hours, enabling it to generate electricity even at night or during cloudy conditions, thus providing continuous electricity generation.

Meanwhile, another ambitious project emerged across the Atlantic: the Ivanpah plant, inaugurated in 2014 in the Mojave Desert, was the largest solar thermal plant at the time, with a capacity of 392 megawatts. The design included three central towers, each 140 meters tall, and a total of 173,500 heliostats. This facility operates with steam at a temperature of 550 degrees Celsius and integrates two natural gas steam boilers for auxiliary and nighttime conservation purposes. Unfortunately, in January 2025, co-owner NRG Energy announced plans to close the plant beginning in early 2026, not due to technological failure but rather because of the competitive pricing of photovoltaic solar panels.

While international projects have garnered significant attention, Mexico is also making strides in solar energy for electricity production. Around 2016, a collaborative project was initiated between the Institute of Renewable Energies at UNAM and the University of Sonora to establish an Experimental Central Tower Field in the Sonoran Desert. This facility features a 32-meter-high tower and 40 heliostats of varying surface areas. Serving as both a testing plant and a laboratory, it aims to design, test, and evaluate solar trackers, heliostats, solar receivers, thermal storage systems, and control systems.

This experimental field has provided a foundation for Mexico”s next step: demonstrating that solar thermal energy can compete with major electricity generation methods. On August 26, 2025, the Mexican government, through the Ministry of Energy and the Federal Electricity Commission, announced plans to construct two solar thermal power towers in Baja California Sur, expected to generate 100 megawatts through continuous operation over 11 hours. These towers, surrounded by circles of light in the desert, symbolize the potential for harnessing solar energy as a partner in the energy transition. Perhaps Aureliano never envisioned that the great magnifying glass he dreamed of for warfare would transform into a tool capable of electrifying thousands of homes with the limitless energy of the sun.