As homes and cities worldwide celebrate Diwali, the Indian festival of lights, physicist Rupamanjari Ghosh draws parallels between this joyous occasion and the advancements in quantum science. Ghosh, a prominent figure in quantum optics and former vice chancellor of Shiv Nadar University, views Diwali as a metaphorical representation of the triumph of knowledge over ignorance.

“Diwali originates from Deepavali, which translates to a “row of lights”. It symbolizes the victory of light over darkness, good over evil, and knowledge over ignorance,” Ghosh remarks. “Each scientific discovery mirrors a Diwali celebration—a triumph of knowledge.” With 2025 designated as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, Ghosh feels this message resonates strongly during this period. “It has taken us a century since the advent of quantum mechanics to reach a point where quantum technologies are on the brink of transforming our daily lives,” she adds.

Ghosh has been recognized as this year”s Institute of Physics Homi Bhabha lecturer. The Institute of Physics and the Indian Physical Association have collaborated on this initiative since 1998 to foster discussions on global challenges through the lens of physics while offering physicists opportunities for international exposure and professional development. Her upcoming online lecture, titled “Illuminating quantum frontiers: from photons to emerging technologies,” is scheduled for October 22.

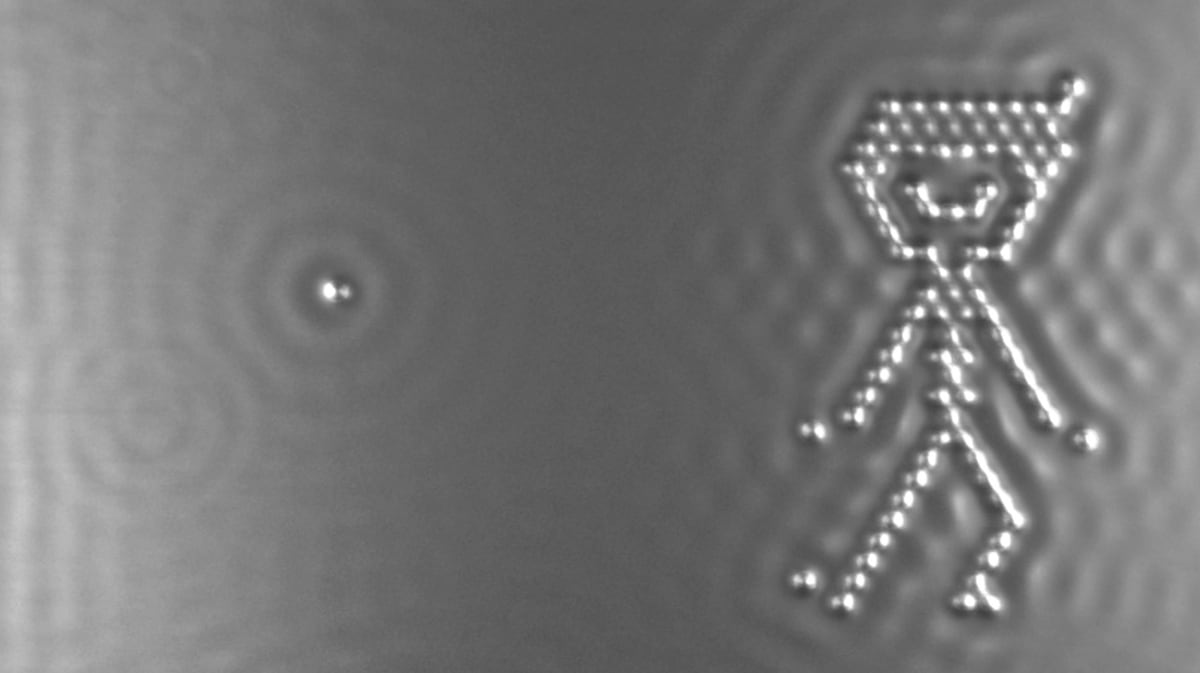

Her journey in physics began in the mid-1980s when she and American physicist Leonard Mandel showcased a novel quantum source of twin photons using spontaneous parametric down-conversion. This discovery, where a high-energy photon divides into two lower-energy, correlated photons, challenged classical explanations and validated early concepts of quantum nonlocality. Today, these entangled photon pairs serve as foundational elements in quantum communication and computation.

“We are experiencing yet another Diwali of enlightenment,” she states, emphasizing the interplay between theoretical knowledge and experimental innovation. Ghosh likens the interconnectedness fostered by Diwali lamps to the concept of quantum entanglement, highlighting how both establish connections that transcend physical boundaries.

Her research further explores this idea, as her team investigates methods to map quantum states of light onto atomic excitations. Techniques such as “slow-light” utilizing electromagnetically induced transparency allow for the storage and retrieval of photons, which are crucial for long-distance quantum communication. “Symbolically, it is akin to transferring the flame from one diya to another. We are not merely dispersing light; we are also preserving, encoding, and transmitting it. Success is rooted in connection and collaboration,” she explains.

Ghosh asserts that in the realm of quantum physics, “darkness” is not devoid of content. “In quantum optics, even vacuums are rich with fluctuations that contribute to our comprehension of the universe.” Her research team examines the transition from quantum to classical systems, employing techniques such as error correction and coherence preservation to mitigate decoherence—the degradation of quantum behavior due to environmental interactions.

She warns that some vulnerabilities in quantum communication systems arise from human errors rather than scientific limitations. “Security is only as strong as its weakest engineering component,” she cautions. Beyond the technical challenges, Ghosh finds a deeper significance in these issues, linking them to the understanding of time and the irreversible evolution of the universe.

Diwali, for Ghosh, also serves as a reminder of the need for inclusivity in scientific fields. “No area should remain in darkness,” she emphasizes. “Science flourishes through diversity, as varied teams pose broader inquiries and envision richer solutions. This is not just ethically sound; it enhances scientific progress.”

She highlights that equity entails recognizing uniqueness rather than enforcing uniformity. “Innovation thrives on diversity. In fields like quantum science, where intuition is frequently challenged, different cognitive styles are invaluable.” Ghosh expresses concern over the hidden biases in academia that can hinder visibility and opportunity for underrepresented groups. “Institutions must address and dismantle these biases through both structural and cultural transformations.”

Her vision extends beyond gender representation; she advocates for a holistic approach to life and work. “Work and life should not be seen as opposing forces to be balanced. Instead, we should create harmony among all life dimensions—work, family, education, and personal rejuvenation,” she concludes. As the diyas are lit this Diwali, Ghosh”s insights remind us that both classical and quantum light serve as moral forces that unite, illuminate, and endure. “Every advancement in quantum science is another stride in the timeless journey from darkness to light,” she reflects.

This article is part of Physics World“s contributions to the 2025 International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, aiming to enhance global awareness of quantum physics and its applications. Stay connected with Physics World and its international partners for ongoing coverage of the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology.