A groundbreaking study has uncovered that during the Victorian era in Manchester, affluent doctors and engineers cohabited with working-class individuals in what were traditionally deemed “slums.” This unexpected revelation stems from research conducted by Emily Chung, a historian at Cambridge University, who analyzed data from the digitized 1851 census to map the residential patterns of various social classes in the city.

Chung”s findings challenge long-held beliefs about social segregation in 1850s Manchester. Historians have often relied on the observations of Friedrich Engels, who noted stark class divisions during his visit in 1842. Engels depicted a city where different social strata resided in distinct areas, with the working class confined to certain neighborhoods while the middle and upper classes enjoyed more spacious suburban living. However, Chung”s research provides new insights, indicating that many middle-class residents shared buildings and streets with working-class artisans.

According to Chung, over 60% of the buildings occupied by the wealthiest residents also housed unskilled laborers, and more than 10% of the population within Manchester”s slums were from the employed upper classes. “We have been misled to believe that the wealthier classes isolated themselves in townhouses or villas,” Chung stated. “In reality, I found professionals like doctors, engineers, and teachers living alongside impoverished weavers and spinners.”

The researcher employed ordnance survey maps, commercial directories, and the 1851 census to accurately link individuals to their residential addresses. Her meticulous efforts involved mapping up to 700 buildings each day, a task that remains beyond the capabilities of current artificial intelligence technologies. Chung observed that the commercial district in the southwestern part of Manchester exhibited a notably higher degree of social diversity compared to the more residential areas in the north and east.

Interestingly, even in Ancoats, a neighborhood notorious for its working-class reputation and highlighted by Engels, around 10% of its inhabitants belonged to the wealthier employed classes. Overall, the working class made up an average of 79.3% of Manchester”s population at the time.

Chung expressed surprise at her findings, noting, “I began my research in the city center, expecting to find a clear pattern of segregation, but I consistently encountered evidence of social mixing throughout Manchester.” She highlighted that a significant portion of the middle class might have viewed their residences as transitional spaces, while others appreciated the convenience of living close to their workplaces, especially in an era before the popularity of commuter trains.

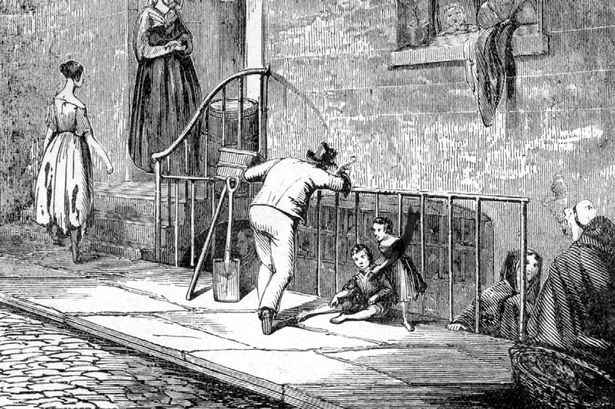

During the first half of the 19th century, Manchester”s rapid population growth outpaced housing construction, resulting in a unique urban development. Chung remarked, “The city expanded almost organically, with developers eager to maximize profits from limited land. This led to the stacking of multiple households within single structures.” While different social classes lived in close proximity, the design of their residences often minimized interaction, with walls and routines creating barriers between them.

Chung observed that while middle and upper classes had flexible access to shops, factory workers often had to wait until paydays to purchase necessities. Unlike other cities such as London and Liverpool, which thrived with daytime activity, Manchester”s public spaces were often deserted. She noted that the city”s streets rarely saw both weavers and doctors at the same time.

Religious practices also reflected class divides, with middle-class individuals drawn to church services while working-class people frequented the numerous pubs scattered throughout the city. Chung pointed out that churches had ceased to provide relief as they had under earlier welfare laws, which made many poor attendees feel ashamed. This led to a situation where churches often kept different classes apart, with morning services catering to the affluent and afternoon or evening services attracting the working class.

Conversely, pubs emerged as welcoming spaces for the working-class population. However, as soon as individuals stepped outside, law enforcement was often present to enforce social separation, compelling working-class individuals to retreat to less visible parts of the city. Chung noted, “Even small gatherings of working-class men were dispersed by police, who aimed to maintain a clean and orderly public realm dominated by the middle and upper classes.”

Ultimately, Chung”s research underscores the need to reassess the perceptions of class dynamics in Victorian Manchester by comparing them with tangible geographic patterns. She concluded, “Understanding these realities allows us to reconstruct a more accurate picture of life in the city, shedding light on how these perceptions were formed.” One lingering question remains regarding the shared outdoor toilets among various families from different social classes, a topic that was rarely documented at the time. Chung speculated that the middle classes likely relied on chamber pots, reducing their dependence on shared facilities.