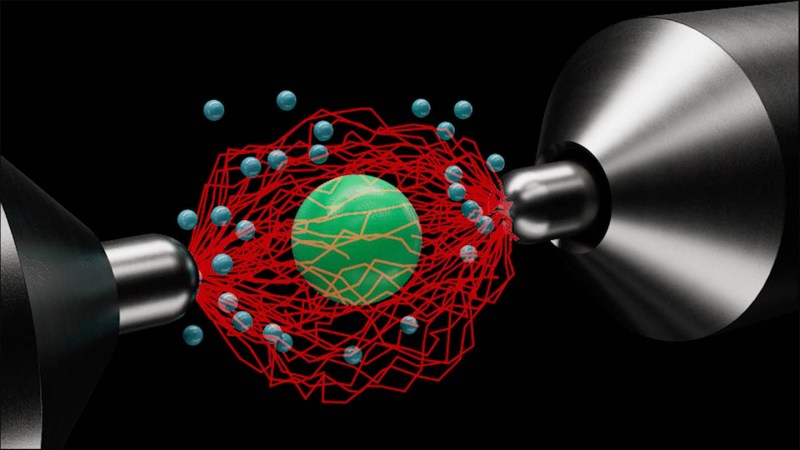

The latest research reveals that a small glass sphere, measuring just 5 micrometers in diameter, behaves like the hottest engine ever created, reaching an effective temperature of 13 million kelvins. This extraordinary finding, detailed in a forthcoming article in Physical Review Letters, sheds light on the peculiar physics of extreme temperatures at the microscale.

The glass sphere is suspended in a near-vacuum environment by an electric field, and its motion is amplified by a jittery voltage that causes it to vibrate intensely. Despite its effective temperature being comparable to the sun”s core, touching the glass sphere would not result in a burn. The effective temperature stems from the energy of the sphere”s motion rather than the movements of its individual molecules, which typically define temperature.

“It is moving as if you had put this object into a gas that was that hot,” explained James Millen, a physicist at King”s College London and coauthor of the study. “It moves around like crazy.”

This phenomenon is especially notable given the sphere”s minuscule size. John Bechhoefer, a physicist at Simon Fraser University, acknowledged the achievement, stating, “Creating effective temperatures that high at that scale is very nice.” He also pointed out that the effective temperature is influenced by the object”s size, suggesting that larger engines might achieve even higher effective temperatures.

High effective temperatures are significant for engine performance. In thermodynamics, which focuses on heat, work, and energy, the glass sphere operates as a heat engine. This type of engine generates mechanical work by absorbing heat from a high-temperature source and transferring waste heat to a cooler sink. The sphere demonstrated a remarkable hot-to-cold temperature ratio of about 100, compared to commercial engines, which typically achieve ratios around 3.

This unique engine enables researchers to explore engine behavior at extreme temperatures and small scales. The team observed considerable fluctuations in the engine”s efficiency, which varied between 10 percent and 200 percent. Intriguingly, there were instances when the engine appeared to operate in reverse, cooling rather than heating.

“Thermodynamics down at the microscale is really, really weird. I really think it”s as unintuitive as something like quantum mechanics,” Millen remarked. Understanding these dynamics is essential, as they reflect the realities within biological cells, where structures like proteins are subjected to the random movements of their environment.

The researchers aspire to leverage this engine to investigate the mechanics of tiny biological engines, such as kinesin, a motor protein responsible for transporting cargo inside cells. Unlike conventional engines, the glass sphere does not perform any practical functions. “No one would really say, “Vroom vroom, that”s an engine,”” Millen stated. Instead, he described it as “a perfect analog of an engine,” offering scientists a tool for studying the operations of such small devices.

As the particle navigates through the electric field, the temperature it experiences fluctuates. This phenomenon, known as position-dependent diffusion, plays a vital role in biological functions like protein folding. Physicist Uroš Delić from TU Wien in Vienna, who was not part of this research, commented that achieving even one of the engine”s characteristics—extreme temperature, a high hot-to-cold temperature ratio, or position-dependent diffusion—would make for an interesting experiment. “This work combines all three, so that”s quite cool—or hot,” he added.