New research has revealed that our brains assess various food characteristics in mere milliseconds, long before we consciously decide what to eat. This study, published in the journal Appetite, explores how quickly we process aspects such as taste, healthiness, and price when faced with food options.

The study examines the rapidity with which our brains react to food imagery, demonstrating that many attributes are reflected in brain activity just hundreds of milliseconds after viewing food. This response occurs significantly faster than the time it takes for individuals to make conscious dietary choices.

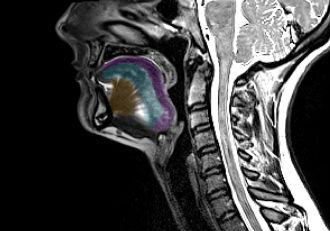

Utilizing electroencephalography to monitor electrical brain activity with precise timing, researchers observed participants as they viewed images of various food items, including snacks, meats, fruits, and desserts. Participants were asked to evaluate these foods based on several factors such as healthiness, tastiness, calorie content, and familiarity.

By employing machine learning techniques, the researchers compared the patterns of brain activity against the participants” ratings, determining if the foods that elicited the most significant differences in ratings also corresponded to notable variances in brain activity. The results confirmed that information regarding food attributes was indeed represented in brain activity.

Notably, the study found that attributes like healthiness, calorie content, and familiarity were processed in the brain as quickly as 200 milliseconds after the food image appeared. This rapid processing occurred before individuals could consciously recognize the food. In contrast, attributes related to taste and appetite were reflected in brain activity slightly later.

These findings suggest that our brains automatically assess multiple aspects of food almost simultaneously, influencing our dietary decisions even before we become consciously aware of them. Interestingly, the study indicated that healthiness was recognized in brain activity earlier than tastiness, which challenges some previous research. This discrepancy may be attributed to the machine learning methods used, which may have been more adept at identifying subtle patterns in brain responses.

Moreover, the study identified two critical dimensions in food evaluation: the “processed” dimension, which relates to how natural or processed a food is, and the “appetising” dimension, which encompasses the taste and familiarity of the food. Both dimensions were evident in brain patterns approximately 200 milliseconds after viewing the food.

The implications of this research extend to scenarios where visual cues are the primary basis for food choices, such as grocery shopping or navigating food delivery apps. It provides insights into how individuals make quick judgments in these contexts. The brain imaging techniques employed in this study may also aid in determining whether strategies that focus on the healthiness of foods could alter rapid evaluations and potentially improve dietary choices.

While this study concentrated on visual imagery, other sensory experiences, such as smell and sound, likely play a significant role in food-related decision-making. Future research aims to explore how these additional sensory features influence our brain”s processing of food, particularly when the actual food is present.

Violet Chae received support from a Research Training Program Scholarship during this research, while Daniel Feuerriegel and Tijl Grootswagers obtained funding from the Australian Research Council.