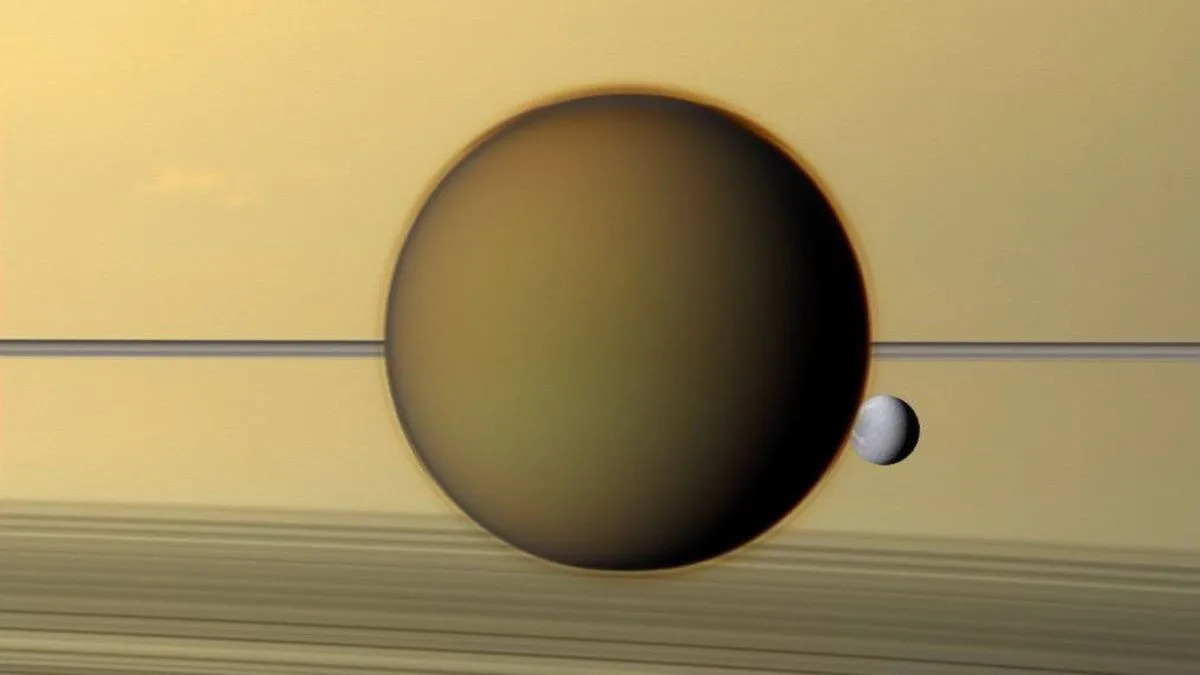

A groundbreaking discovery regarding Saturn”s moon Titan has raised questions about established chemical principles. A team led by chemist Fernando Izquierdo-Ruiz from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden suggests that in Titan”s frigid environment, certain molecules, which were previously considered incompatible, can form novel solids not observed elsewhere in the Solar System. “These are very exciting findings that can help us understand something on a very large scale, a moon as big as the planet Mercury,” noted chemist Martin Rahm of Chalmers University.

Titan is a uniquely intriguing body in our Solar System, with its methane and hydrocarbon lakes showcasing complex chemical interactions that resemble prebiotic conditions necessary for life. While this does not confirm the existence of life, it provides a valuable opportunity to explore how life could potentially arise under similar circumstances. A key element in prebiotic chemistry is hydrogen cyanide, which can produce essential compounds like nucleobases and amino acids under optimal conditions. Hydrogen cyanide is notably abundant on Titan.

This compound is also a polar molecule, characterized by an uneven distribution of electrons that results in a partial charge. Typically, polar molecules repel non-polar substances, such as methane and ethane, which are prevalent on Titan. This phenomenon is similar to how water (polar) does not mix with oil (non-polar); it takes more energy to combine them than to keep them separate.

The research into hydrogen cyanide”s behavior on Titan was initiated by scientists at NASA”s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who aimed to investigate the molecule”s fate after it forms in Titan”s atmosphere. They conducted experiments at approximately -180 degrees Celsius (-292 degrees Fahrenheit), which reflects Titan”s surface temperatures. In these conditions, hydrogen cyanide crystallizes while methane and ethane remain liquid. Although changes were observed in the mixtures during analysis, the exact nature of these changes remained unclear, prompting collaboration with Chalmers chemists.

“This led to an exciting theoretical and experimental collaboration between Chalmers and NASA,” stated Rahm. “We posed a somewhat unconventional question: Could the measurements be attributed to a crystal structure where methane or ethane interacts with hydrogen cyanide? This contradicts the chemistry rule that “like dissolves like,” indicating that these polar and non-polar substances should not be able to combine.”

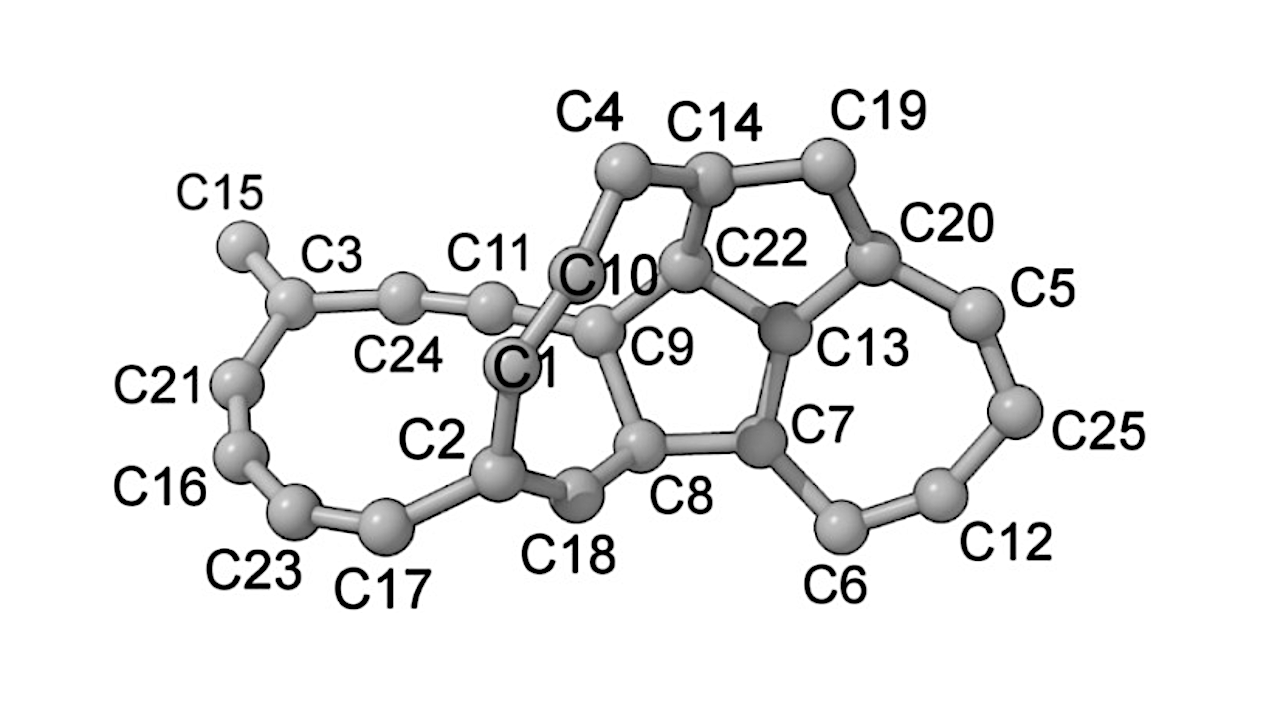

The experimental setup involved creating a chamber cooled to around -180 degrees Celsius, allowing researchers to grow hydrogen cyanide crystals. They introduced methane, ethane, propane, and butane into this environment and utilized Raman spectroscopy to observe molecular vibrations. The analysis revealed slight yet significant changes in the oscillations of hydrogen cyanide after exposure to methane and ethane, suggesting an interaction rather than mere coexistence. The observed shifts indicated that the hydrogen bonds within hydrogen cyanide were being influenced by the presence of methane and ethane.

Subsequently, the research team employed computer modeling to validate their findings, discovering that methane and ethane were able to integrate into the gaps of the hydrogen cyanide crystal lattice, forming stable co-crystals at Titan-like temperatures. Under such extreme conditions, the molecules exhibit less thermal movement than they would at higher temperatures, allowing them to interact in ways that are typically not possible.

“The unexpected interaction between these substances may reshape our understanding of Titan”s geology and its unusual landscapes of lakes, seas, and sand dunes,” Rahm explained. However, the true significance of this unusual chemistry may take years to confirm, as the anticipated Dragonfly probe is not expected to land on Titan until 2034.

In future research, the scientists aim to explore what other non-polar substances might interact favorably with hydrogen cyanide under the right conditions. The findings have been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.