Standard MRI scans of the tongue may play a significant role in the early detection and ongoing monitoring of Motor Neurone Disease (MND). A study led by Dr. Thomas Shaw at The University of Queensland reveals that individuals with MND, also referred to as ALS, often exhibit reduced tongue muscle size, particularly when they experience difficulties with speaking or swallowing.

Dr. Shaw noted that the tongue consists of eight interconnected muscles, each serving distinct functions such as eating, swallowing, and speaking. In patients with MND, these muscles progressively weaken and diminish over time. “Detecting and tracking this symptom early could assist patients and healthcare providers, particularly in accessing early clinical trials,” he explained.

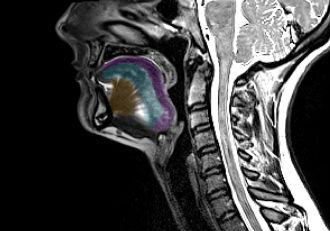

The investigation into tongue muscles in MND patients has been traditionally invasive and challenging. Fortunately, a standard brain MRI often includes images of the tongue. The research team analyzed over 200 historical MRI scans, which included subjects both with and without MND. By employing a mix of AI-assisted techniques and advanced imaging, they achieved accurate measurements of tongue muscle volume and shape.

Significant differences were found when comparing the scans of individuals with MND to those without. Previous studies indicated that MND symptoms affecting the mouth, tongue, throat, and neck correlate with shorter survival times compared to symptoms beginning in the limbs. “Our findings echoed this, with lower tongue volumes associated with poorer prognoses,” Dr. Shaw stated. This measurement could potentially provide insights into life expectancy for those diagnosed with MND and facilitate quicker diagnosis, which is crucial for timely clinical trial enrollment.

Co-author and speech pathologist Dr. Brooke-Mai Whelan from UQ”s School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences emphasized the complexity of the tongue, which performs numerous coordinated movements daily that often go unnoticed until they fail. “When tongue function declines, it can lead to dangerous swallowing conditions and make speech difficult to comprehend,” Dr. Whelan added. MND patients often report that losing the ability to speak is more distressing than losing the ability to eat, drink, or walk.

Understanding which specific tongue muscles are affected in MND can lead to strategies that compensate for this loss, such as adjusting speech patterns to utilize unaffected muscle groups. Furthermore, it can facilitate preparations for interventions like voice banking, which involves recording a person”s natural voice for use in communication devices following speech loss.

Dr. Shaw highlighted that the methodologies and data from this research are publicly accessible to support the broader scientific community. “Currently, there is a lag of approximately 12 months between the onset of MND symptoms and the subsequent diagnosis. Our goal is to expedite access to treatments, support services, clinical trial enrollments, and voice banking,” he stated. This approach may also be applicable to a wide array of existing MRI datasets, offering new insights into various health issues, including speech disorders and cancer.

The findings of this research are published in Computers in Biology and Medicine. The multidisciplinary team involved researchers from UQ”s Queensland Digital Health Centre, School of Biomedical Sciences, School of Psychology, Medical School, as well as the Royal Brisbane and Women”s Hospital, Griffith School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queensland Health, Neuroscience Research Australia, Google DeepMind, and the University of Sydney.

Dr. Shaw is affiliated with the Centre for Advanced Imaging at the Australian Institute for Bioengineering and Nanotechnology and the UQ Centre for Motor Neuron Disease Research at the School of Biomedical Sciences.