In a groundbreaking study, researchers have revealed that the so-called dinosaur mummies found in eastern Wyoming”s Lance Formation are not preserved skin but rather intricate clay masks. This area, known for its rich collection of prehistoric fossils, has yielded several remarkably intact specimens, including those of the large duck-billed dinosaur, Edmontosaurus annectens.

Dr. Paul Sereno, a paleontologist and professor at the University of Chicago, led a team that explored the reasons behind the exceptional preservation of these dinosaurs in a site they refer to as the “mummy zone.” The team”s research builds on the early 1900s discoveries made by fossil hunter Charles Sternberg, who unearthed two Edmontosaurus specimens with strikingly preserved features, including a fleshy crest and scales.

Despite the extraordinary nature of these findings, Sereno noted that these were not actual dehydrated skin, as previously thought. Instead, the latest investigation, involving advanced techniques like CT scanning and electron microscopy, revealed a thin layer of clay, less than one-hundredth of an inch thick, covering the dinosaur remains.

“It”s so real-looking, it”s unbelievable,” Sereno stated about the clay”s appearance. He suggested that the term “rendering” might be more accurate than “impression” when describing the clay”s detailed likeness to the dinosaur”s skin.

The research indicates that during the Late Cretaceous Period, the region experienced cycles of drought and heavy rainfall. The original mummy discovered by Sternberg likely died during a drought, followed by a flash flood that buried the carcasses in sediment. As the bodies decayed, a film of bacteria formed, which attracted clay particles from the sediment, leading to the creation of the clay mask that preserved the dinosaur”s morphology.

Dr. Anthony Martin, a professor at Emory University who did not participate in the study, explained that clay minerals have an inherent ability to adhere to biological surfaces, thereby capturing detailed features like scales and spikes.

Dr. Stephanie Drumheller-Horton, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Tennessee, commented on the significance of understanding the fossilization process. “If we can understand how and why these fossils form, we can better target where to look to potentially find more of them,” she explained.

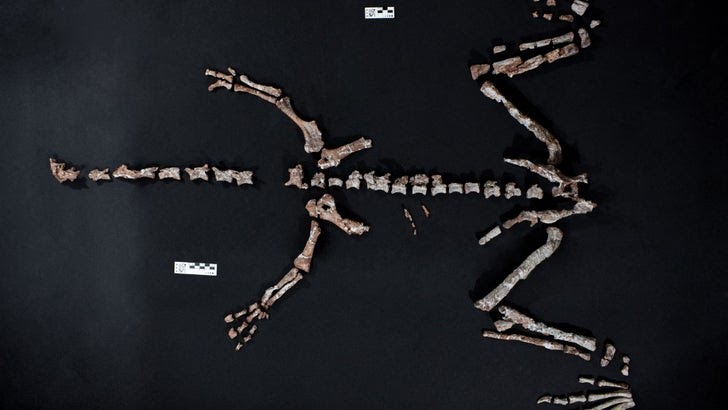

After analyzing two recently discovered mummies, the research team produced an updated understanding of what Edmontosaurus might have looked like, revealing a fleshy crest along the neck and a row of spikes along the tail. The findings also indicated that this dinosaur had hooves, marking it as the oldest known land animal with this feature and the first hooved reptile, as Sereno humorously noted, “Sorry, mammals, you didn”t invent it.”

The study was published in the journal Science, providing new insights into the preservation of these ancient creatures and enhancing our understanding of their appearance and biology.