Researchers have unveiled a novel type of ice, designated as ice XXI, which forms at ambient temperatures under specific pressure conditions. Traditionally, ice is perceived simply as frozen water, but its structure is far more complex. Water, composed of just two elements—hydrogen and oxygen—can crystallize into over 20 distinct types of ice, each characterized by unique internal arrangements of atoms.

For over a century, scientists have investigated various ice forms, driven not only by scientific curiosity but also by the necessity to comprehend how water behaves in extreme conditions, which may include environments capable of supporting alien life. Among the notable findings in this field are ice XIX and ice VIIt, the latter of which is found deep within Earth”s mantle or on watery exoplanets. The Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science (KRISS) has made a significant breakthrough with the identification of ice XXI, an unprecedented form of ice.

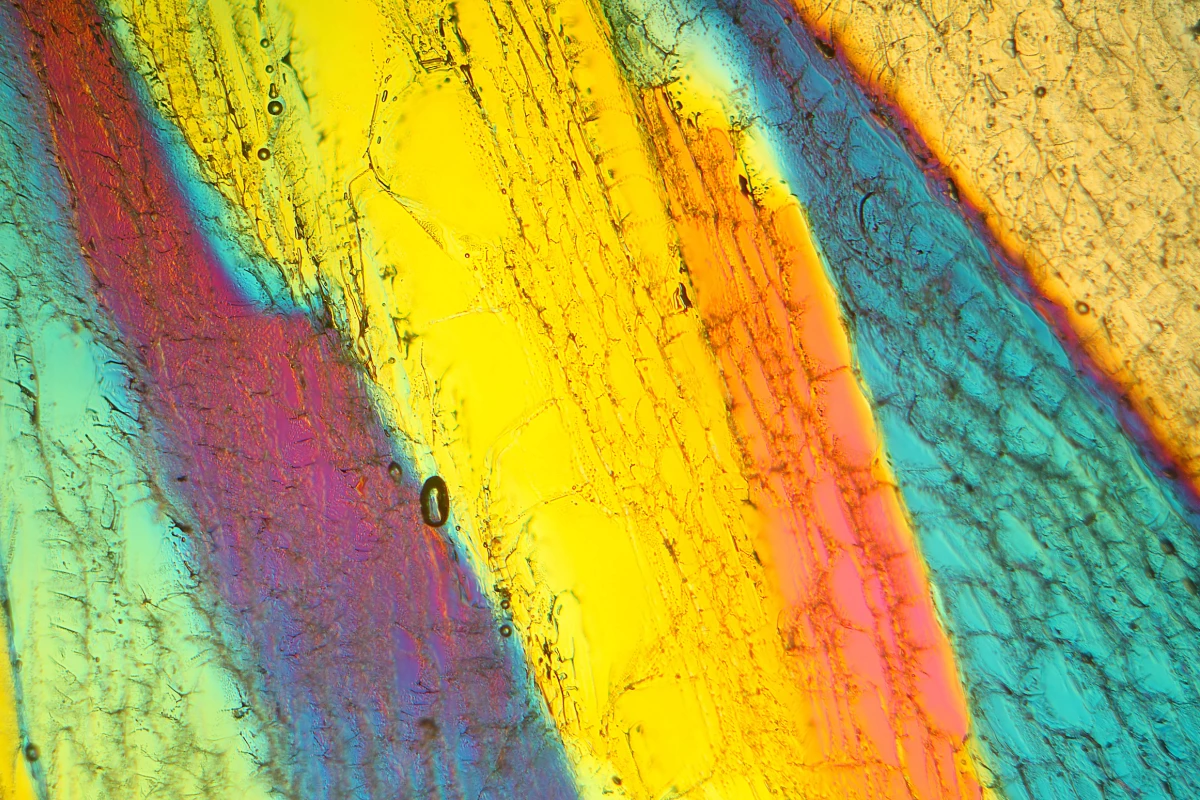

Employing a sophisticated setup that integrates diamond anvils and X-ray lasers, the researchers observed the behavior of super-compressed water at room temperature. Contrary to expectations, instead of transitioning to ice in one smooth process, the water underwent multiple freeze–melt cycles within the pressure range typically associated with ice VI formation. It was within this unique environment that ice XXI emerged.

Ice XXI is distinguished by its unique atomic structure, setting it apart from the more than 20 known types of ice. It is also metastable, implying it can persist in an unstable state for a period, thus providing insights into ice formation under pressure. “Rapid compression of water allows it to remain liquid at higher pressures, where it would ordinarily crystallize into ice VI,” explained KRISS scientist Geun Woo Lee.

The research team created high-pressure conditions using diamond anvil cells, filling a tiny metal chamber with ultra-pure water. By employing high-speed cameras, laser-based sensors, and real-time monitoring tools, they meticulously documented the freezing and melting processes of water at room temperature. They adjusted the pressure rhythmically to capture the transformation with remarkable precision, tracking variations in structure, pressure, and volume.

To pinpoint the exact moment water changes into this exotic ice, powerful X-ray beams from a synchrotron were utilized. The scattered X-ray signals were recorded and analyzed through a program known as DIOPTAS. Two types of detectors were employed, one operating at a rapid pace and the other at a steadier rate, enabling the team to observe the intricate transformation of water into ice.

Simultaneously, scientists conducted molecular dynamics simulations employing two models: SPCfw45 and TIP4P/Ice46. While TIP4P/Ice serves as a rigid water model with fixed molecular angles and bond lengths, SPCfw offers more flexibility, allowing water molecules to bend and stretch. Despite their differing rigidity, both models revealed similar trends regarding how water responds to pressure, which aligned with experimental results.

The findings indicated that when water is super-compressed at room temperature, it does not freeze in a singular, straightforward manner. Instead, it experiences several freeze–melt loops before ultimately forming the known type of ice VI. However, nestled within this pressure range, researchers discovered ice XXI, which crystallizes at approximately 1.6 gigapascals and exhibits a body-centered tetragonal crystal structure. Ice XXI is peculiar in that it possesses higher energy than MS-ice VII at room temperature, rendering it less stable.

In a separate high-pressure experiment utilizing X-ray lasers, the team found that water does not follow a singular freezing pathway; in fact, it can take at least five different routes, even at room temperature. “With the unique X-ray pulses of the European XFEL, we have uncovered multiple crystallization pathways in H2O, which was rapidly compressed and decompressed over 1,000 times using a dynamic diamond anvil cell,” added Geun Woo Lee.

Co-researcher Rachel Husband noted that these discoveries suggest the potential existence of a broader range of high-temperature metastable ice phases and their associated transition pathways, which could yield new insights into the composition of icy moons.

The study has been published in Nature Materials.