Recent laboratory investigations indicate that some organic molecules identified in the plumes of Saturn”s moon Enceladus might originate from space radiation instead of from its subsurface ocean. This revelation adds complexity to the evaluation of these compounds” relevance to astrobiology.

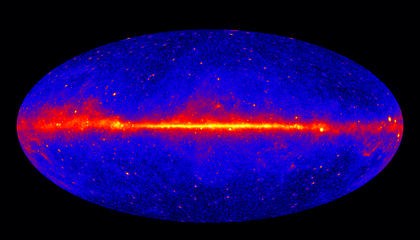

Enceladus conceals a global ocean beneath its icy exterior, ejecting material into space through fissures near its south pole. This results in plumes composed of tiny ice particles that can extend for hundreds of kilometers. While most of this ejected material returns to the moon”s surface, some remains in orbit, contributing to Saturn”s E ring, the planet”s outermost and broadest ring.

Between 2005 and 2015, NASA”s Cassini spacecraft conducted multiple flybys of these plumes, detecting a variety of organic compounds. Initially, this was interpreted as evidence for a chemically rich and potentially habitable environment beneath the ice. However, the latest study posits that radiation—rather than biological processes—may account for the presence of at least some of these organic molecules.

To investigate the influence of space radiation, a research team led by planetary scientist Grace Richards, a postdoctoral researcher at the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome, simulated conditions similar to those near Enceladus”s surface. They created a mixture of water, carbon dioxide, methane, and ammonia, cooling it to minus 200 degrees Celsius in a vacuum chamber. The mixture was subsequently bombarded with water ions, which are significant in the radiation environment surrounding the moon.

This radiation triggered a series of chemical reactions, yielding a mix of molecules, including carbon monoxide, cyanate, ammonium, various alcohols, and molecular precursors to amino acids such as formamide, acetylene, and acetaldehyde. The formation of these simple molecules suggests that similar radiation-induced reactions could occur on Enceladus.

Richards shared these findings at the Europlanet Science Congress–Division for Planetary Sciences Joint Meeting (EPSC-DPS 2025) in Helsinki, Finland, and published a comprehensive report in Planetary and Space Science.

The implications of this research prompt questions regarding the true origins of the organic molecules observed in Enceladus”s plumes. Are they sourced from the moon”s hidden ocean, formed in space, or generated near the surface after exiting the moon”s interior? While this study does not rule out the possibility of a habitable ocean on Enceladus, Richards advises caution in linking the detected molecules” presence to their origin and potential role in biochemistry.

“My experiments do not discredit the idea of Enceladus”s habitability,” Richards stated. However, she emphasized the necessity of understanding all processes that modify the material before making inferences about the ocean”s composition.

Planetary scientist Alexis Bouquet from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) at L”Université d”Aix-Marseille, who was not part of the study, highlighted the importance of conducting similar experiments to prepare for future missions to Enceladus and to interpret data from current missions targeting Jupiter”s icy moons.

These missions include NASA”s Europa Clipper, which aims to explore Europa, and the European Space Agency”s JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer), set to visit Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa. The intense radiation surrounding Jupiter makes these experimental insights particularly relevant.

In a related investigation, researchers led by planetary scientist Nozair Khawaja from the Freie Universität Berlin and the University of Stuttgart reported new types of organic molecules detected during Cassini”s 2008 flyby of Enceladus. This analysis revealed the presence of ester and ether groups, along with chains and cyclic species containing double bonds of oxygen and nitrogen. While these molecules could have inorganic origins, Khawaja noted that they enhance Enceladus”s habitability potential.

The findings indicated that complex organic molecules exist in freshly expelled ice grains from the vents, suggesting that the ice did not remain in space for long, possibly only a few minutes. This brief exposure raises questions about whether space radiation had sufficient time to synthesize the organic molecules detected by Khawaja”s team.

Both studies underscore the intricate chemistry of Enceladus, reinforcing its status as a key site in the search for extraterrestrial life or its building blocks. Enceladus possesses the three essential requirements for life: liquid water, an energy source, and a diverse array of chemical elements.

Although accessing the subsurface ocean may be challenging, the plumes present a unique opportunity to analyze an extraterrestrial liquid ocean. Current studies are underway to develop a potential ESA mission focused on Enceladus, which may include high-speed flybys through the plumes and possibly a lander at the south pole. Insights from the recent studies will inform the design of instruments and the interpretation of future findings.

“There is no better place to search for life than Enceladus,” Khawaja concluded.