Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have introduced a groundbreaking approach that enables the examination of atomic nuclei using a compact laboratory setup, eliminating the need for expansive and powerful particle accelerators. This advancement was detailed in a study published on October 23 in the journal Science.

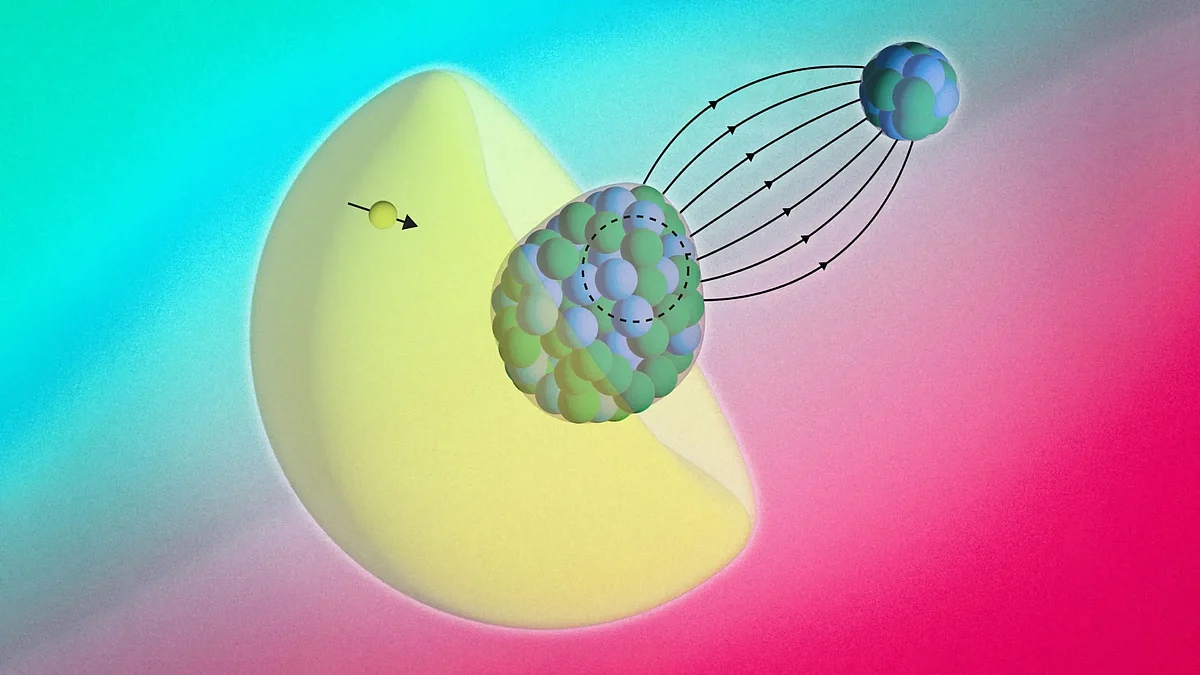

The team focused on measuring the energy levels of electrons surrounding a radium atom that is chemically bonded to a fluoride atom, forming radium monofluoride. By utilizing the molecular environment as a miniature particle collider, they restricted the movement of electrons, enhancing the likelihood that some electrons would briefly pass through the nucleus.

To achieve this, the researchers synthesized molecules of radium monofluoride (RaF), which consist of a radium atom paired with a fluoride atom. Within these molecules, certain electrons can occasionally get close enough to the nucleus to interact with it directly. By meticulously analyzing slight variations in the energy of these electrons, the scientists were able to confirm that nuclear penetration had occurred. This innovative technique effectively transforms the molecule into a small-scale particle collider, facilitating the study of nuclear dynamics on a more manageable scale.

This method could significantly advance our understanding of how magnetism is distributed within atomic nuclei, shedding light on the behavior of protons and neutrons as minute magnetic sources. Furthermore, gaining insights into this nuclear structure may contribute to addressing one of the most profound questions in physics: the observed predominance of matter over antimatter in the universe.

“Our results lay the groundwork for subsequent studies aiming to measure violations of fundamental symmetries at the nuclear level,” stated Ronald Fernando Garcia Ruiz, co-author of the study and an associate professor of physics at MIT. The unique properties of radium make it particularly suitable for these experiments due to its nucleus”s distinctive pear-shaped asymmetry, which increases its sensitivity to subtle symmetry-breaking effects.

The MIT team intends to further refine their technique by cooling and aligning the RaF molecules more precisely, which will enable them to map nuclear structures with even greater accuracy.