The extraordinary longevity of the Greenland whale, known scientifically as Balaena mysticetus, has long fascinated scientists. This remarkable species, which can grow up to 18 meters long and weigh over 80 tons, is believed to live for more than 200 years, making it one of the longest-living mammals on Earth. Indigenous peoples, particularly the Inuit, have a deep understanding of these majestic creatures, relying on them for sustenance in the harsh Arctic environments of northern Canada, Alaska, Siberia, and Greenland.

Researchers have been investigating how these whales manage to avoid diseases such as cancer, especially considering the biological paradox known as Peto”s paradox. This concept highlights that larger animals, which have more cells and a longer lifespan, should theoretically have a higher cancer risk. However, studies show that smaller mammals, including rodents, actually exhibit higher rates of cancer than elephants and whales. The recent findings suggest that the longevity of the Greenland whale may be due to a unique mechanism that enhances their ability to repair DNA.

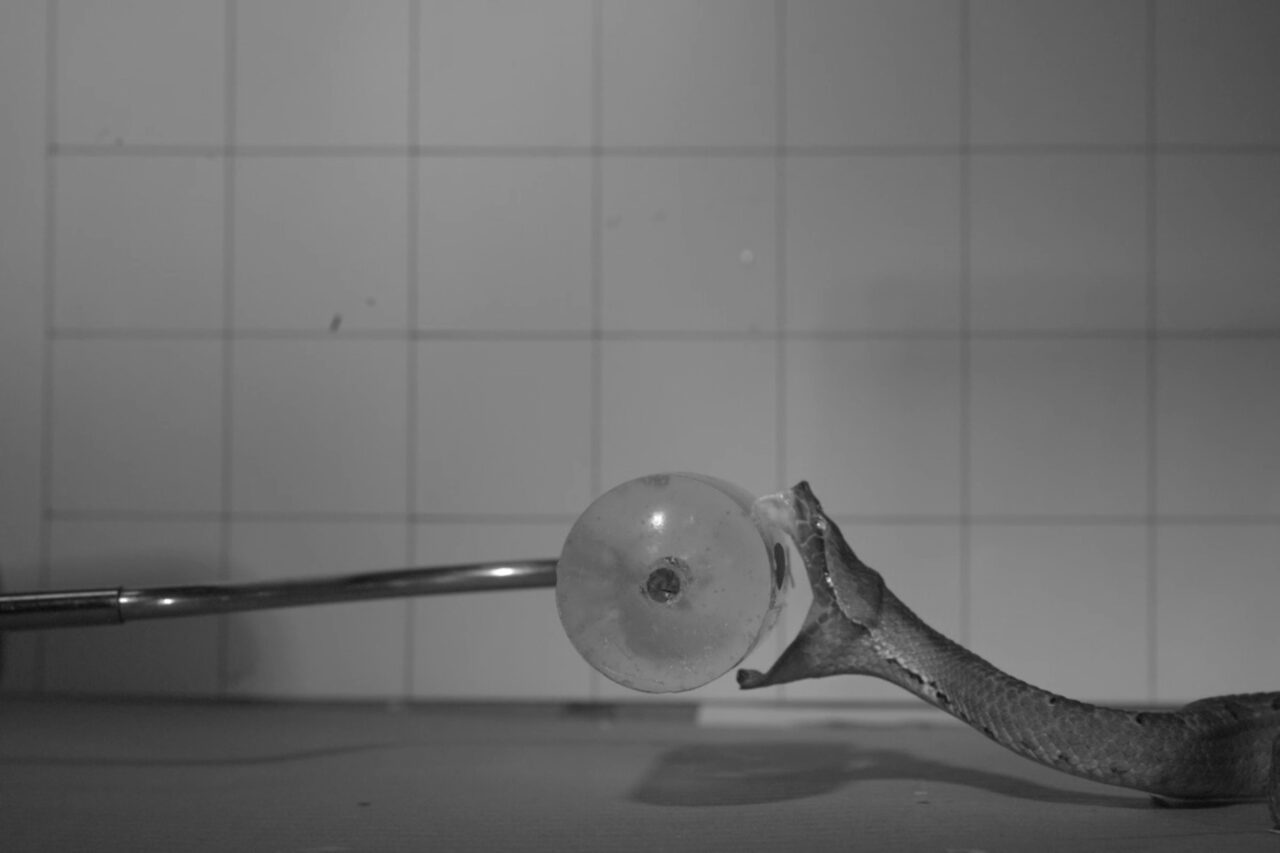

Published in a recent issue of a scientific journal, a study led by Jan Vijg from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine investigated the cellular responses of Greenland whale fibroblasts to DNA damage. Contrary to the well-known role of the p53 gene, which is crucial in eliminating harmful mutations, the researchers found that Greenland whale cells exhibited lower basal activity of p53 and did not increase apoptosis—programmed cell death—following DNA stress, unlike human cells. This indicates that the p53 signaling pathway may not significantly contribute to the cancer resistance observed in these whales.

The study identified another key player in this process: a protein called Cirbp. Vera Gorbunova, co-director of the University of Rochester”s Aging Research Center and a co-author of the study, explained that Cirbp promotes DNA repair and helps the whales adapt to cold conditions. The research team found that when exposed to oncogenic stimuli like ultraviolet radiation, Greenland whale cells required fewer mutations to become malignant than human cells. However, they also had a lower incidence of such mutations, suggesting a greater efficiency in repairing DNA damage.

In their experiments, the researchers noted a high expression of Cirbp in the fibroblast and tissue samples from the whales. While humans produce this protein, the levels are significantly lower than in Greenland whales. Notably, increasing Cirbp levels in fruit flies resulted in extended lifespans, reinforcing the potential benefits of enhancing DNA repair mechanisms.

Despite their remarkable longevity, Greenland whales do not hold the record for the oldest living animals. That title belongs to the Icelandic clam (Arctica islandica), which can live up to 507 years. Among vertebrates, the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) is known to reach ages of up to 400 years, according to a 2016 study published in the journal Science.