The healthcare practices of ancient Egypt have played a significant role in shaping modern medicine, according to researchers from the University of Manchester. In their new book, published by Liverpool University Press, Professor Rosalie David and Dr. Roger Forshaw present evidence that reveals the ancient Egyptians established an organized health service accessible to all, regardless of social status.

This research is unique in that it examines healthcare from the perspectives of ancient physicians, patients, and nurses. The authors argue that the ancient Egyptian medical system can be viewed as a precursor to contemporary healthcare, featuring roles akin to modern consultants and general practitioners who treated individuals at home or in hospital-like settings.

Nurses played a vital role in patient care, and midwives, predominantly women, held a respected position within society. Interestingly, some records suggest that these midwives earned higher wages than doctors. Medical training for aspiring practitioners often took place in temples, where student medics were typically male relatives of established doctors.

Evidence from mummy discoveries indicates that individuals suffering from chronic illnesses received assistance from nurses and support staff throughout their lives. Patients requiring more intensive care would stay in small chambers connected to temples, such as the one in Denderah, where they would be treated by priest-doctors. This treatment could be compensated either through direct contributions from patients, such as food or goods, or through state support for certain vulnerable groups, resembling modern-day healthcare systems.

The effectiveness of this healthcare model was notable. As long as individuals survived past their first five years, their life expectancy aligned closely with that of many people in Victorian Britain, estimated between 30 and 40 years. Treatments deemed “rational,” such as bandaging for fractures, were implemented for visible ailments, and palliative care options existed for those facing terminal conditions. For instance, community doctors often prescribed Balanites oil, derived from the Desert Date tree, to treat bilharzia, a severe illness caused by parasitic worms; this treatment remained in use in some medical practices until fifty years ago.

However, treatments classified as “irrational,” especially for conditions like mental illness where causes were less apparent, often relied on spells and magical practices. The researchers gathered much of their information from medical papyri unearthed across Egypt, which detail various diseases, diagnoses, and treatment methods, including herbal medicines, surgical procedures, and magical incantations. Currently, only twelve of these ancient medical texts are known to exist from a history spanning over three millennia, with the possibility of more being discovered in future excavations or recognized within modern library collections.

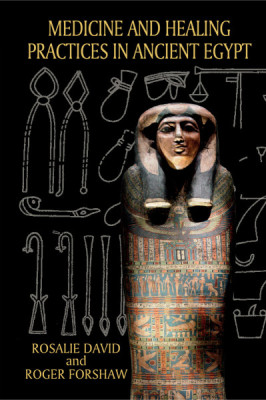

Professor David noted that the New Kingdom (1550 BCE – 1069 BCE) and the Greco-Roman Period around the commencement of the common era marked significant advancements in Egyptian healthcare, which likely began around 3000 BCE. Their book, titled Medicine and Healing Practices in Ancient Egypt, illustrates the direct connections between ancient Egyptian medical practices and the evolution of healthcare in European, Arabic, and ancient Greek traditions.

Professor David expressed enthusiasm about the paperback release of their book, emphasizing its potential to educate the public, healthcare professionals, and enthusiasts of Egyptology about the substantial contributions of ancient Egyptian medicine to current medical systems. She also commented on the misconception of ancient Egypt as a violent society, stating that the societal organization and care for its citizens were advanced compared to other civilizations of the time.