A research team has uncovered a significant breakthrough in the sustainable production of ethylene, a vital ingredient in plastic manufacturing. The enzyme methylthioalkane reductase, produced by the bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum, facilitates the creation of ethylene in anaerobic conditions while avoiding carbon dioxide emissions.

Current industrial practices primarily rely on fossil fuels for ethylene production, prompting scientists to explore renewable alternatives. Although bacterial enzymes show promise as catalysts for this process, only a limited number can generate ethylene without releasing CO2. The discovery of methylthioalkane reductase sparked excitement among researchers, as it allows for ethylene production without oxygen and without carbon emissions.

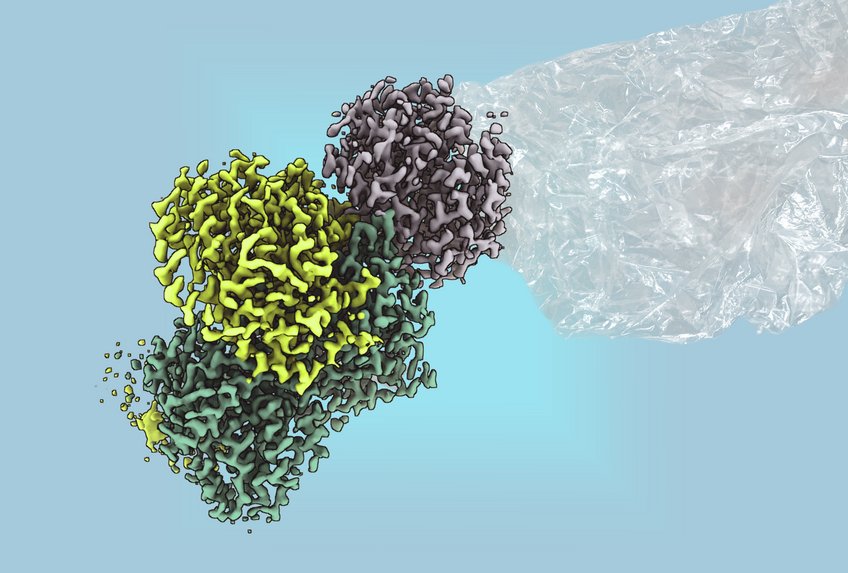

However, the enzyme”s sensitivity to oxygen posed challenges for detailed research. Until recently, methylthioalkane reductase could only be investigated in cell cultures, leaving many questions about its biotechnological applications unanswered. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology, led by Johannes Rebelein, have now successfully purified the enzyme and elucidated its structure in collaboration with RPTU Kaiserslautern.

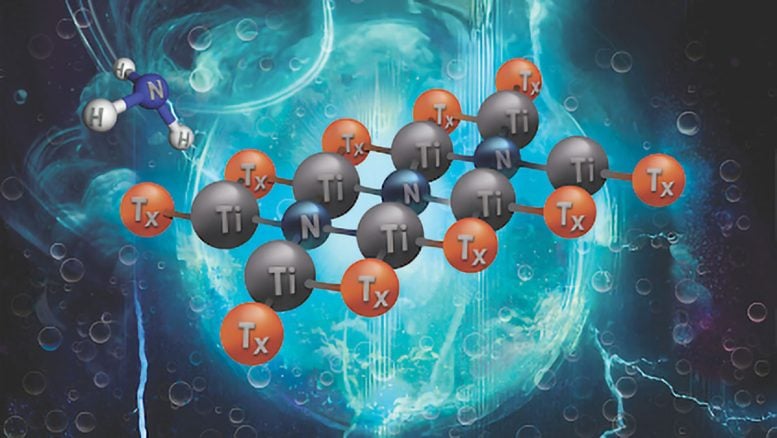

The team”s analysis revealed that the enzymatic reaction is powered by large, complex iron-sulfur clusters, previously believed to exist solely in nitrogenases, some of the earliest enzymes known to science. According to Ana Lago-Maciel, a doctoral student and lead author of the study, “The reaction is driven by large, complex iron-sulfur clusters, which were previously thought to occur only in nitrogenases.”

This marks the first time a non-nitrogenase enzyme has been identified containing these metal clusters. Nitrogenases are responsible for converting atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form for living organisms, thanks to their intricate iron-sulfur structures, which are deemed one of the “great clusters of biology.” The newfound understanding of methylthioalkane reductase not only reveals its biochemical and structural properties but also highlights a significant source of hydrocarbons.

“The enzyme has remarkable versatility,” Rebelein notes. “It can sustainably produce a range of hydrocarbons, including ethylene, ethane, and methane.” The enzyme”s ability to produce various hydrocarbons differs from nitrogenases and provides insights into how the reactivity of metal clusters is influenced by the protein structure.

This study lays the groundwork for harnessing these reductases in biotechnology, allowing researchers to tailor their product output to meet specific needs. Additionally, the findings offer intriguing perspectives on the evolutionary history of these important biological clusters. “Our results suggest that structurally similar enzymes utilized these clusters for reductive catalysis long before nitrogenases evolved,” Rebelein explains. This discovery represents a pivotal shift in our comprehension of a critical phase in Earth”s biological history.