While weather control remains elusive, scientists have developed methods to encourage precipitation through a technique known as cloud seeding. This process typically involves the aerial dispersal of tiny particles of silver iodide into targeted clouds. These particles serve as nuclei for water molecules, which then cluster together, forming ice crystals that grow large enough to precipitate as rain or snow.

Researchers at TU Wien have recently shed light on the intricate atomic interactions involved in this process, using advanced microscopy and computer simulations. Their findings, published in Science Advances, indicate that silver iodide possesses two distinct surfaces, yet only one effectively facilitates ice nucleation. This discovery enhances our comprehension of precipitation mechanisms and could inform the development of more efficient materials for stimulating rainfall.

Understanding Ice Formation Through Surface Structure

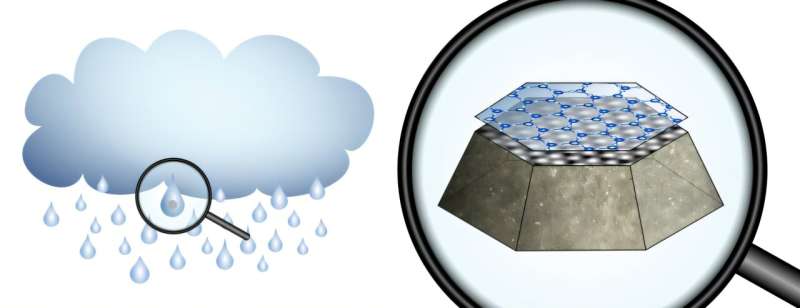

“Silver iodide exhibits hexagonal structures that mirror the sixfold symmetry characteristic of snowflakes,” explains Jan Balajka from the Institute of Applied Physics at TU Wien, who led the study. “The atomic spacing in these structures also closely resembles that of ice crystals. Previously, it was thought that this structural resemblance accounted for silver iodide”s efficiency as an ice nucleus. However, our detailed analysis reveals a more nuanced mechanism.”

The atomic structure of the surface responsible for ice nucleation differs significantly from that of the interior of the crystal. When a crystal of silver iodide is cleaved, one side is terminated with silver atoms while the opposite side features iodine atoms. “Our research shows that both the silver-terminated and iodine-terminated surfaces undergo reconstruction, albeit in entirely different manners,” notes Johanna Hütner, a key contributor to the experiments. The silver-terminated surface maintains a hexagonal layout conducive to ice layer growth, while the iodine-terminated surface rearranges into a rectangular configuration that disrupts the sixfold symmetry necessary for ice formation. “Only the silver-terminated surface plays a role in promoting nucleation,” Balajka adds. “The ability of silver iodide to initiate ice formation cannot be solely attributed to its bulk crystal structure; the atomic-level restructuring at the surface is critical, an aspect that has been largely overlooked until now.”

Experimental and Computational Approaches to Nucleation

The research team employed two complementary methodologies to investigate these phenomena. They conducted experiments in conditions of ultrahigh vacuum and at low temperatures, depositing water vapor onto small crystals of silver iodide. The resulting structures were analyzed using high-resolution atomic force microscopy. “A significant challenge was conducting all experiments in complete darkness,” Hütner explains. “Silver iodide is highly sensitive to light, a property that historically made it useful in photographic technology. We only illuminated the samples with red light when necessary within the vacuum chamber.”

Simultaneously, the team utilized density functional theory, an advanced computational technique for modeling atomic-scale interactions, to simulate the surfaces and the water structures that form on them. “These simulations enabled us to identify the most energetically stable atomic arrangements,” Andrea Conti, who conducted the calculations, elaborates. “By accurately modeling the interface between silver iodide and water, we could observe how the initial water molecules organize on the surface to initiate an ice layer.”

“It is astonishing that we relied on a rather vague, phenomenological explanation for silver iodide”s nucleation behavior for so long,” remarks Ulrike Diebold, head of the Surface Physics Group at TU Wien. “Understanding ice nucleation at such a fundamental level is vital for atmospheric physics, and this atomic-scale insight lays the groundwork for evaluating whether other materials could also function as effective nucleation agents.”