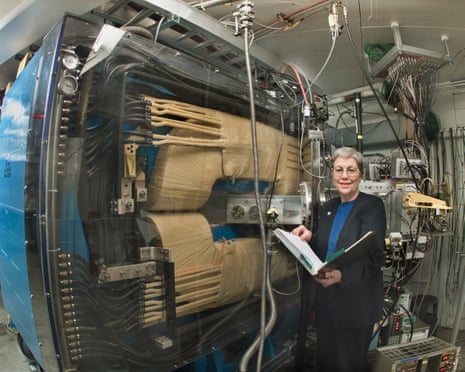

Darleane Hoffman, a distinguished nuclear chemist whose groundbreaking work on transuranic elements significantly advanced the understanding of nuclear fission, passed away at the age of 98. Her research, conducted primarily at the University of California”s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and previously at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, redefined the scientific community”s approach to these superheavy radioactive elements.

Hoffman”s exploration of transuranic elements, which are heavier than uranium, revealed critical insights into their chemical and nuclear properties. These elements are all radioactive and typically have short half-lives, often decaying in mere milliseconds, making them challenging to study. However, during the 1950s, Hoffman recognized that understanding their characteristics could enhance the comprehension of nuclear fission, a process pivotal for the operation of the first commercial nuclear reactors.

Uranium, with an atomic number of 92, was long considered the heaviest naturally occurring element. For decades, scientists believed that transuranic elements, those with atomic numbers greater than 92, were synthetic and did not exist in nature. However, in a remarkable discovery in 1971, Hoffman identified plutonium-244 in rocks from a nuclear test site in Nevada, challenging previously held beliefs. She noted, “For years it was assumed uranium-238, with a half-life of 4.5 billion years, was the heaviest naturally occurring radioactive isotope.” Her findings suggested that plutonium-244 could have formed naturally under conditions similar to those of historical nuclear tests.

This discovery led to an intensified search for ancient rocks capable of containing such elements, culminating in Hoffman”s confirmation of plutonium”s presence in a formation at Mountain Pass Mine in California. Her contributions to nuclear chemistry earned her accolades, including being named one of the “50 Most Important Women in Science” by Discover magazine in 2002.

Born on November 8, 1926, in Terril, Iowa, Hoffman was inspired by her chemistry professor, Nellie Naylor, as well as by the pioneering work of Marie Curie. She graduated from Iowa State College in 1948 and earned her PhD in nuclear chemistry in 1951, marrying fellow student Marvin Hoffman the same year. Shortly thereafter, they both began their careers at Los Alamos, where their two children, Maureane and Daryl, were born.

Hoffman faced challenges early in her career, including skepticism from human resources regarding her capabilities as a chemist. Despite these obstacles, she made significant strides in her field, including the detection of fermium-257, atomic number 100. A pivotal moment occurred while she was recovering from illness, during which she analyzed data concerning fermium and identified inconsistencies with existing fission theories. Her findings indicated that some nuclei split into equal parts, contradicting traditional expectations.

In recognition of her expertise, Glenn Seaborg, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering transuranic elements, invited her to join him at LBNL in 1978. Hoffman also became the first woman to lead a scientific department at Los Alamos, heading the nuclear chemistry division. Later, she succeeded Seaborg at LBNL and continued her research on heavy elements, contributing to the identification of hassium and confirming the existence of seaborgium.

Her work had far-reaching implications, influencing areas ranging from medical applications of radioisotopes to advancements in nuclear reactor safety and the detection of nuclear proliferation. Hoffman also played a role in developing safety protocols for nuclear waste management and investigating radioactive leaks at test sites. She once remarked, “There are many practical issues my work can address, and many discoveries yet to be made.”

Throughout her career, Hoffman received numerous honors, including the National Medal of Science awarded by President Bill Clinton in 1997 and the Priestley Medal from the American Chemical Society in 2000. She is survived by her two children and three grandchildren. Darleane Christian Hoffman left a remarkable legacy in nuclear chemistry and will be remembered for her exceptional contributions to science.