The Nobel Prize in Physics 2025 will be awarded to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for their significant contributions to the understanding of macroscopic quantum tunneling and energy quantization in electrical circuits. This article explores the implications of their groundbreaking research.

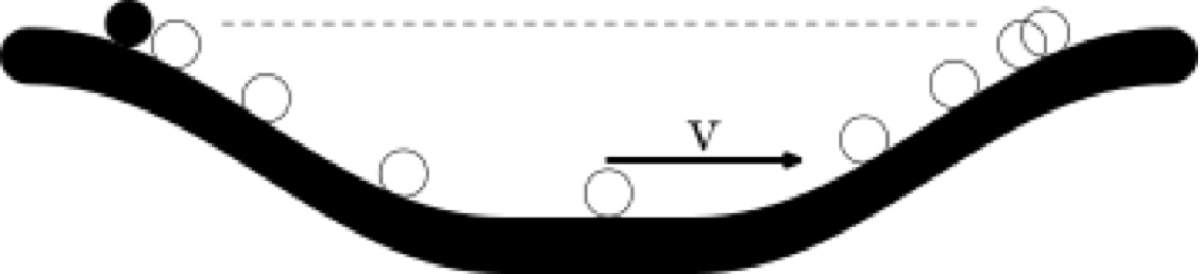

To illustrate fundamental principles of energy conservation, consider a marble placed near the edge of a deep bowl. When released, it accelerates towards the bottom, then climbs up the opposite edge, slowing down until it eventually comes to rest. This motion will repeat, but with diminishing heights until the marble permanently settles at the bottom. This simple experiment demonstrates energy conservation, where gravitational potential energy transforms into kinetic energy as the marble moves and then back into potential energy as it rises.

As the marble rolls, it also generates sound and warmth, dissipating some energy as acoustic and thermal energy, preventing it from reaching its original height. From such experiments, we learn about different forms of energy while recognizing that the total energy in a closed system remains constant.

Focusing on potential energy, which is determined by configuration, and kinetic energy, which is determined by motion, we note that potential energy can be gravitational, elastic, or even electric. It can be represented as a function U(x), dependent on the system”s configuration x.

In a graphical representation, potential energy U is plotted against configuration x, illustrating total energy E and kinetic energy K. A particle with energy E can only exist in specific regions where its potential energy does not exceed its total energy, preventing it from breaching certain barriers.

Next, consider a piece of metal, like a spoon. Attempting to see through it reveals the opacity of metals, which arises because visible light—an electromagnetic wave—cannot penetrate. Metals” electrons react to electromagnetic fields, creating a shielding effect that nullifies the field within the metal.

However, if light with a frequency greater than that of the plasma frequency of the metal shines on it, the metal becomes transparent. This is because rapid oscillations do not allow electrons sufficient time to respond and create the shielding effect, allowing some light to pass through.

Using a thin metallic film, such as a reflective snack bag, one can observe that while the metal reflects light, a small amount can penetrate if the film is sufficiently thin. This light exists as an evanescent wave, which diminishes after a very short distance within the metal.

Quantum mechanics reveals that particles behave as both waves and particles, allowing electrons to penetrate classically forbidden regions through the process known as tunneling. This principle explains various chemical phenomena, including how electrons escape atoms to form chemical bonds. The scanning tunneling microscope exemplifies practical applications of this principle, enabling scientists to visualize individual atoms on surfaces.

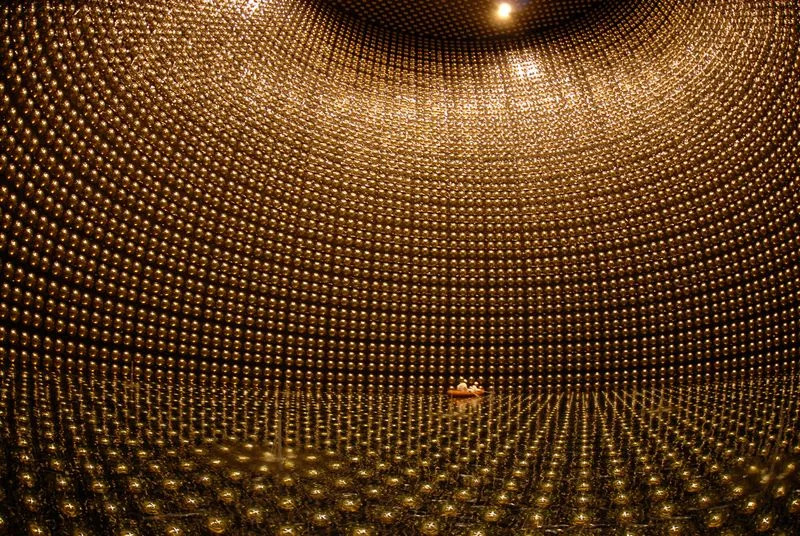

Beyond individual particles, the phenomenon of superconductivity illustrates collective quantum behavior. Certain materials can conduct electricity without resistance at low temperatures, forming pairs of electrons known as Cooper pairs that move in unison, resembling a coordinated dance. The attractive forces between electrons and positive ions in the material allow these pairs to overcome their natural repulsion.

The Josephson Junction is a critical component in this context. It consists of two superconductors separated by a thin insulating barrier, allowing Cooper pairs to tunnel through without energy loss. This discovery has significant implications for quantum computing, as it enables the creation of qubits—quantum bits that can exist in multiple states simultaneously, unlike classical bits.

Experiments conducted by Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis at low temperatures have shown how controlling current across a Josephson Junction can lead to measurable voltage differences, indicating the transition from a trapped state to one of movement, thereby demonstrating quantum behavior on a macroscopic scale.

In summary, the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics recognizes the revolutionary impact of tunneling phenomena and energy quantization in superconducting circuits, paving the way for advancements in quantum computing technologies.