The concept of two black holes orbiting each other has been a topic of speculation for many years, and recent satellite imaging may have provided the first concrete evidence of this phenomenon.

Scientists have long theorized that certain quasars, among the brightest entities in the universe, could harbor pairs of black holes engaged in a gravitational interplay. Now, astronomers assert that they have successfully captured direct radio images of such a pair. Utilizing a combination of ground-based and orbital telescopes, researchers identified two supermassive black holes in the quasar OJ287, located approximately 5 billion light-years away in the constellation Cancer.

These two massive black holes are locked in a 12-year orbital cycle. Although black holes themselves are invisible, their existence is inferred from the high-speed particle jets they emit into space. One of these jets originates from the smaller black hole, while the other is produced by a colossal black hole with a mass equivalent to 18 billion suns, making it slightly over half the size of the largest black holes ever observed.

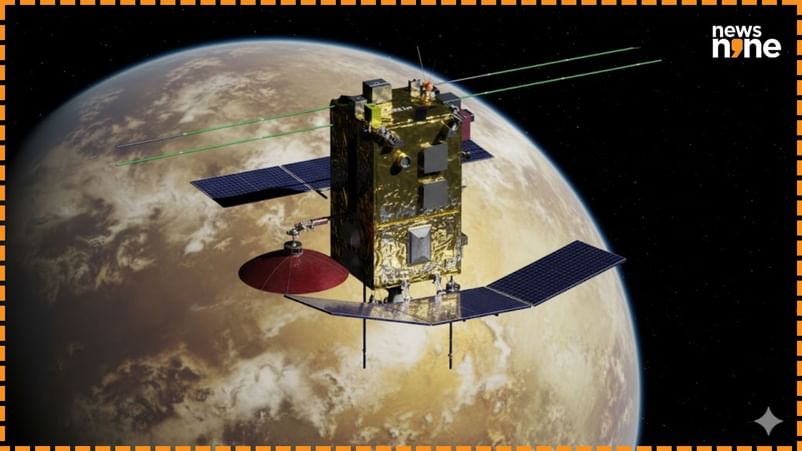

This groundbreaking discovery was detailed in an article published in The Astrophysical Journal on October 9, confirming the existence of black hole pairs—a concept that has been suggested by gravitational theories and indirect evidence for years. The breakthrough was achieved by merging data from terrestrial radio telescopes with observations from the Russian RadioAstron satellite, which operates at a distance that reaches halfway to the Moon.

The resulting images are nearly 100,000 times clearer than those obtained through traditional optical telescopes, providing answers to longstanding questions in astrophysics. OJ287 has fascinated astronomers for over a century, even before black holes became a focal point of scientific inquiry. The quasar was first photographed in the 19th century, although its significance went unrecognized at that time.

In 1982, Finnish astronomer Aimo Sillanpää noted an unusual pattern: the brightness of OJ287 fluctuated with striking regularity every 12 years. This periodic increase in brightness suggested the potential existence of two black holes orbiting one another, with the brightness surges linked to one black hole passing through the accretion disk of the other.

For decades, researchers struggled to validate this theory due to technological limitations. While instruments like NASA”s TESS satellite confirmed the light fluctuations, previous telescopes lacked the precision to distinguish the two black holes. This changed when a team from the University of Turku, led by Mauri Valtonen, employed advanced radio interferometry techniques to analyze OJ287.

Remarkably, their images aligned perfectly with theoretical models, allowing them to precisely locate both black holes as predicted. In a statement, Valtonen noted that while the black holes are inherently undetectable, the glowing gas and jets emitted around them serve as indicators of their presence.

This advancement enables scientists to observe such cosmic events in real-time and, if validated, would confirm the long-held theory that black holes can coexist in pairs. Although gravitational wave detections have suggested the existence of merging black hole pairs, researchers from Turku are cautious and await further high-resolution images to definitively confirm that the observed phenomena are indeed two separate black holes and not merely overlapping jets from a single entity.

Even with the need for additional confirmation, this discovery represents a significant step forward. If their findings can be replicated, OJ287 could stand as the first verified example of two black holes in orbit around each other, potentially shedding light on the formation and evolution of supermassive black holes throughout the universe.