For the first time, astronomers have successfully created a three-dimensional map of the atmosphere of a planet orbiting a distant star, unveiling temperature differences and distinct atmospheric regions on an alien world located 400 light years away. Utilizing the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), researchers tracked subtle changes in brightness as the scorching gas giant known as WASP-18b passed behind its host star. This groundbreaking achievement has allowed scientists to generate a weather map of an exoplanet, transforming these distant celestial bodies from mere points of light into complex environments that can be studied in detail layer by layer.

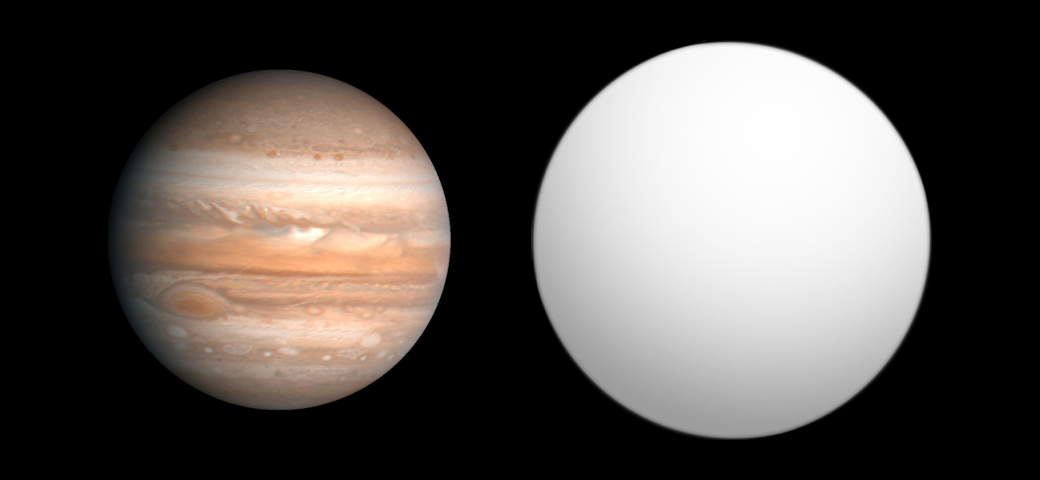

For decades, astronomers have examined Jupiter”s Great Red Spot and its swirling cloud bands through increasingly advanced telescopes, developing a comprehensive understanding of our giant neighbor”s dynamic atmosphere. Now, the mapping of WASP-18b marks a significant advancement, promising to revolutionize our approach to investigating worlds outside our Solar System. WASP-18b, classified as an “ultra-hot Jupiter,” is approximately 400 light years from Earth and has a mass about ten times greater than Jupiter”s. It orbits its star in a mere 23 hours, with temperatures reaching nearly 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit, which is sufficient to break down water vapor molecules present in its atmosphere.

The technique used to achieve this mapping is known as spectroscopic eclipse mapping, which was applied for the first time with data obtained from the JWST. This method is both elegant and highly challenging. As WASP-18b transits behind its star, various sections of the planet move in and out of view. By measuring minute changes in brightness during these transits, researchers can associate specific regions of the planet with observed variations in light, despite the fact that the planet emits less than one percent of the brightness of its star.

The innovation lies in observing these eclipses across multiple wavelengths simultaneously. Different wavelengths of light can penetrate various layers of the atmosphere, as molecules absorb light at specific wavelengths. For example, water vapor absorbs certain infrared wavelengths while allowing others to pass through. By assembling brightness maps across multiple wavelengths and converting these to temperature readings, the researchers constructed a three-dimensional representation that spans latitude, longitude, and altitude.

This resulting map disclosed spectroscopically unique regions across the dayside of WASP-18b, the hemisphere that is permanently oriented toward its star due to tidal locking. These regions exhibit significant variations in temperature and possibly chemical composition, affirming that even planets too distant for direct imaging possess complex and diverse atmospheres that warrant detailed study.

The implications of this technique are vast, as hot Jupiters like WASP-18b comprise hundreds of the over 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, many of which are bright enough for JWST to observe using eclipse mapping. Instead of viewing these distant worlds as simple dots in the sky, astronomers can now begin to understand them as dynamic, three-dimensional environments, mapping their atmospheric features similarly to how we have long mapped the storms of Jupiter.

Future observations with the JWST could further enhance the spatial resolution of these atmospheric maps. Applying this technique to other hot Jupiters will likely reveal a wide range of atmospheric diversity across this category of planets. What started as a proof of concept study of one extreme world may soon evolve into an extensive survey, bringing exoplanets into clearer focus as real entities with geography, weather patterns, and observable atmospheric structures.