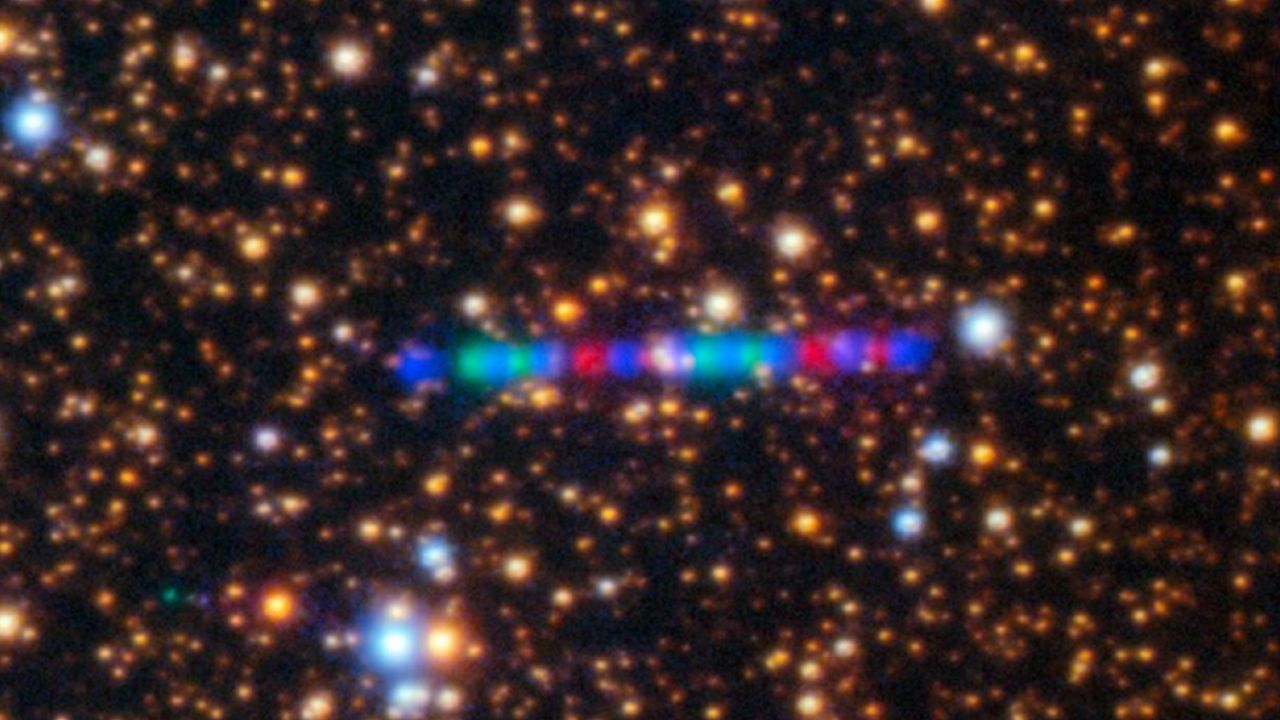

Two spacecraft from the European Space Agency (ESA), Hera and Europa Clipper, are set to fly through the tail of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS within the next two weeks, according to a new paper by researchers Samuel Grand and Geraint Jones. This study, which has been pre-published on arXiv and accepted for publication by the Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society, explores the potential for these missions to detect ions emitted from the comet”s tail as it approaches the Sun.

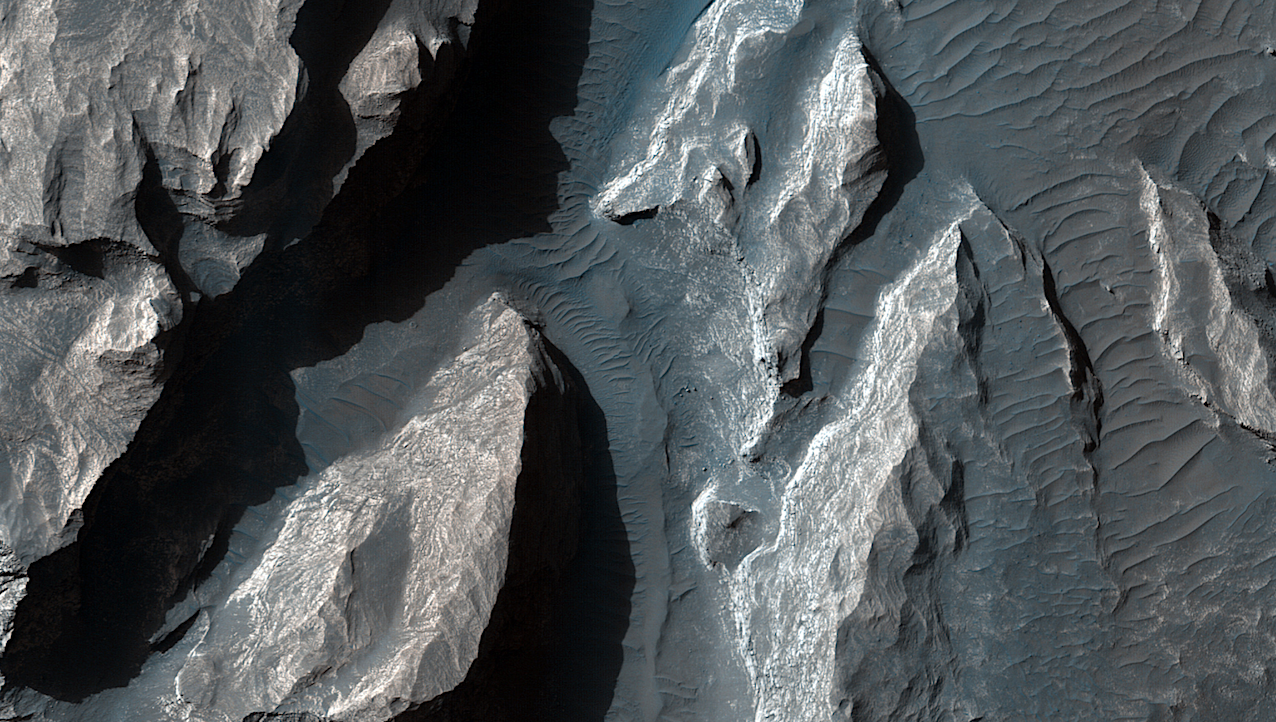

3I/ATLAS is the third known interstellar object discovered, and it has sparked a variety of theories ranging from the speculative to scientifically grounded suggestions. While some theories have proposed using Martian probes to observe the comet, this recent paper takes a different approach: utilizing existing missions that are already on their way to their respective targets.

Hera is heading toward the binary asteroid system Didymos-Dimorphos, which was impacted by the DART mission in 2022. Meanwhile, Europa Clipper is destined for Europa, one of Jupiter”s moons, to study its icy surface. Remarkably, both spacecraft are expected to pass “downwind” of 3I/ATLAS in the coming weeks, with Hera scheduled to make its pass between October 25 and November 1, and Europa Clipper from October 30 to November 6.

The timing presents a unique opportunity for a rapid experimental setup to gather data, despite neither spacecraft being originally designed for this purpose. The tail of 3I/ATLAS has been expanding since its discovery in early June, and recent observations indicate a significant release of water, alongside ions. The comet is anticipated to reach its closest point to the Sun, known as perihelion, on October 29.

However, the trajectory of the tail is affected by solar wind, which disperses the particles along a curved path. Accurately predicting where the spacecraft need to be to collect data on the tail requires precise modeling, which the authors addressed using a model called “Tailcatcher.” This model estimates the path of the cometary ions based on varying solar wind speeds.

Despite the model”s limitations, which depend on solar wind data that is typically available only after the fact, the estimated distance from the central axis of the tail is around 8.2 million kilometers for Hera and 8 million kilometers for Europa Clipper. Such distances remain within a feasible range for collecting data on the tail”s ions, which can extend over vast distances from active comets like 3I/ATLAS.

The challenge lies in the fact that Hera lacks instruments capable of detecting the anticipated ions or the magnetic field changes associated with the comet”s atmosphere. In contrast, Europa Clipper is equipped with a plasma instrument and a magnetometer that could effectively measure these phenomena.

As mission controllers consider this unexpected opportunity, it remains to be seen whether they will be able to adjust their plans in time. If successful, they could achieve the historic milestone of being the first to directly sample the tail of an interstellar comet, a significant accomplishment beyond their original mission objectives.