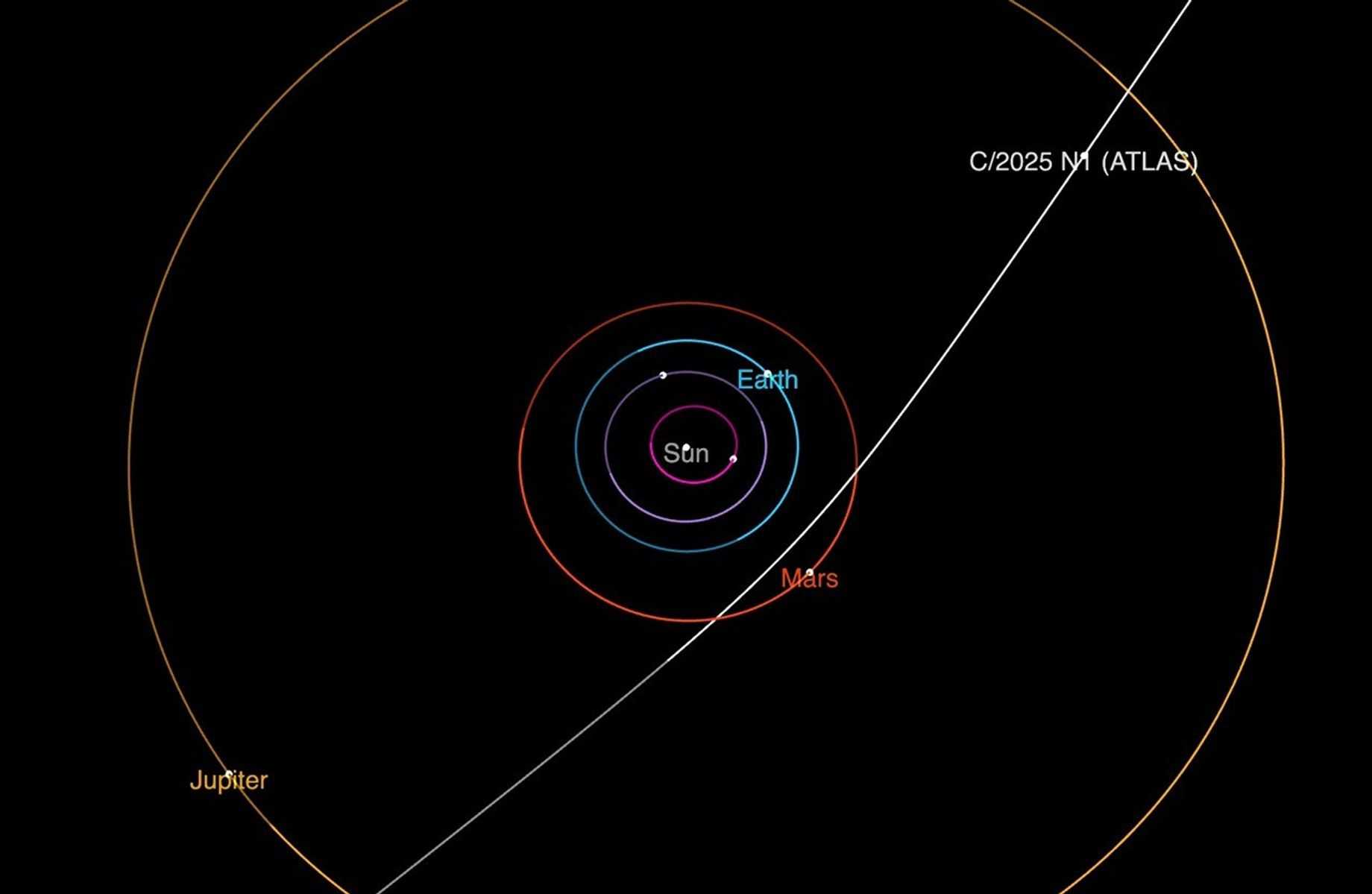

An interstellar comet named 3I/ATLAS, which originated beyond our solar system, has just completed its nearest approach to the sun. While it is now on an outbound trajectory, it will remain within our cosmic vicinity for a while longer. According to EarthSky, the comet passed within approximately 126 million miles (203 million kilometers) of the sun.

Currently, the comet is obscured from view behind the sun when observed from Earth. However, astronomers expect to resume observations in the coming weeks. Darryl Seligman, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Michigan State University, indicated that stargazers using telescopes should be able to spot the comet starting on November 11.

The comet is set to make its closest approach to Earth on December 19, coming within about 168 million miles (270 million kilometers). Fortunately, it poses no danger to our planet, as reported by the European Space Agency.

Since its discovery on July 1, astronomers have been monitoring 3I/ATLAS, marking it as only the third known interstellar object to traverse our solar system. Each observation provides valuable insights into this interstellar body and how its characteristics differ from comets that originated within our solar system.

Comets, often described as dirty snowballs left over from solar system formation, possess a nucleus made up of ice, dust, and rocks. As comets approach stars like our sun, the heat causes them to emit gas and dust, forming their distinctive tails. Astronomers are keen to gather as many observations as possible because the materials released as 3I/ATLAS nears the sun could yield significant information about its composition and the star system from which it came.

Seligman remarked, “When it gets closest to the sun, you get the most holistic view of the nucleus possible. One of the main things driving most cometary scientists is, what is the composition of the volatiles? It shows you the initial primordial material that it formed from.”

To study the comet, scientists have utilized advanced instruments, including the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope, along with various space missions like SPHEREx. Observations from these missions have detected substances such as carbon dioxide, water, carbon monoxide, carbonyl sulfide, and water ice being released from the comet as it approaches the sun. Preliminary estimates suggest that 3I/ATLAS is between 3 billion and 11 billion years old, according to a study co-authored by Seligman and doctoral student Aster Taylor from the University of Michigan.

For context, our solar system is thought to be around 4.6 billion years old. Seligman explained that carbon dioxide transitions from a solid to a gas at temperature changes more readily than most elements, indicating that this comet has likely never come close to another star before its interaction with the sun.

Although the comet became difficult to observe with ground-based telescopes in October, it remained visible to missions like the PUNCH (Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere) and SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory). On October 3, 3I/ATLAS also made its closest approach to Mars, coming within 18.6 million miles (30 million kilometers) of the planet and its orbiting spacecraft.

Despite the government shutdown that has limited data sharing from NASA missions observing the comet since October 1, the ESA missions, including Mars Express and ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, attempted to document 3I/ATLAS in October. The cameras on these missions are focused on studying the bright surface of Mars, but the ExoMars orbiter managed to capture the comet as a faint white dot. Nick Thomas, principal investigator of the orbiter”s camera, noted, “This was a very challenging observation for the instrument,” as the comet was estimated to be 10,000 to 100,000 times fainter than typical targets.

Additionally, the ESA“s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) is expected to observe 3I/ATLAS in November using multiple instruments, despite the comet being farther from the spacecraft than during its observations by the Mars orbiters. However, astronomers do not anticipate receiving the data until February, given the pace at which the spacecraft transmits information back to Earth. Seligman concluded, “We”ve got several more months to observe it, and there”s going to be amazing science that comes out.”