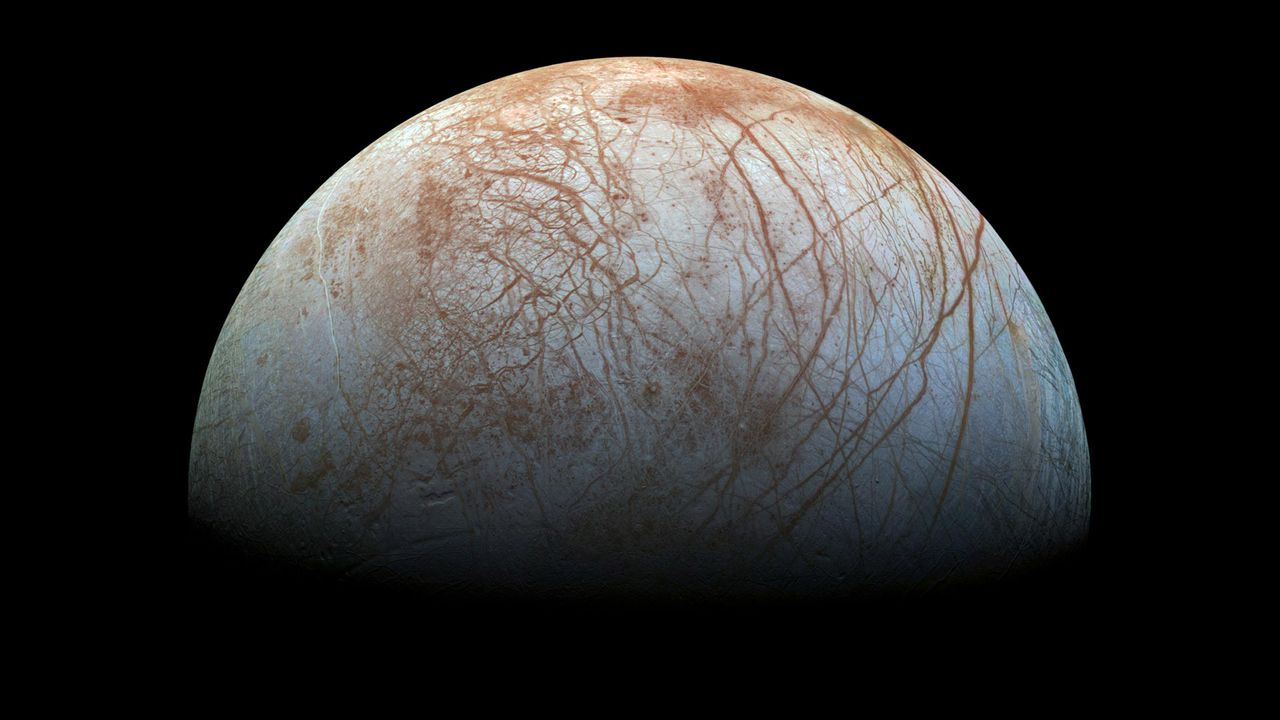

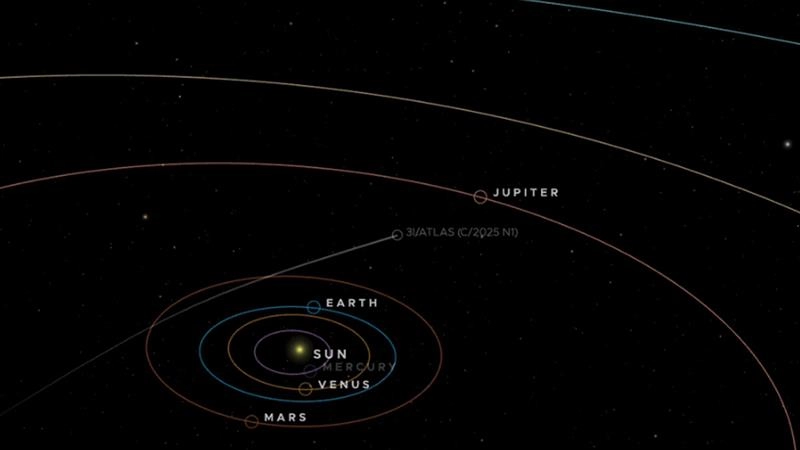

Researchers have introduced a groundbreaking laser-based drilling concept that could transform the exploration of ice-covered celestial bodies within our solar system. This innovative technology aims to penetrate the icy surfaces of moons such as Jupiter”s Europa and Saturn”s Enceladus, as well as other frozen regions including permanently shadowed lunar craters and ice-rich soils near the Martian poles.

Scientists at the Institute of Aerospace Engineering at Technische Universität Dresden in Germany have developed a laser drill that can create deep, narrow channels in ice while minimizing both mass and energy consumption. “We have engineered a laser drill that allows for deep and energy-efficient access to ice without the increased weight associated with mechanical drills and melting probes,” explained Martin Koßagk, the lead author of the study.

Conventional drilling methods can become cumbersome as they require heavier equipment to extend rods deeper into ice, while melting probes typically rely on extensive power sources and long cables. The new laser drill addresses these challenges by performing all operations from the surface. It utilizes a focused beam to vaporize ice, a process termed sublimation, allowing the vapor to escape through a narrow borehole, which can be used for collecting gas and dust samples.

The samples can then be analyzed for their chemical make-up and density, providing vital insights into the thermal properties and geological history of the celestial bodies being studied. While traditional lasers may not be the most energy-efficient instruments, this laser drill operates by vaporizing only a tiny section of ice, leading to overall lower energy consumption compared to electric heaters. It is also more effective in ice layers rich in dust, enabling deeper drilling without the need for additional mass or energy.

Koßagk noted that this technology makes subsurface exploration of icy moons more feasible, allowing for detailed analysis of ice composition and density. This could improve our understanding of heat transport and ocean depths on moons like Europa and Enceladus, while also supporting research on crust formation.

On Earth, the laser drill could assist in analyzing subsurface materials in ice-bearing craters or soils, facilitating geological studies beyond surface layers. The team”s prototype operates at approximately 150 watts and has a projected weight of about 9 pounds, maintaining its mass regardless of depth—whether at 33 feet or 6 miles.

Initial tests have shown success, with the prototype drilling through ice samples approximately 8 inches long under laboratory conditions and achieving greater depths in field tests conducted in the Alps and Arctic. During these tests, the system reached drilling speeds close to 1 meter per hour with 20 watts of laser power, and up to 3 meters per hour in loose or dusty ice.

Despite its potential, the laser drill has limitations. It cannot operate effectively in stone or dust layers devoid of ice. In such scenarios, a new borehole would need to be created from the surface to bypass the obstacle. “It is crucial to use the laser drill alongside other measuring instruments,” Koßagk added, suggesting the use of radar tools to detect larger impediments.

Water-filled crevasses also present challenges; the drill would need to pump out water flowing into the borehole before continuing its work. However, drilling in these areas could reveal the chemical signatures of potential habitats for microbial life, with remnants of ancient bacteria possibly detectable in collected samples.

The next steps for advancing this laser drill technology include miniaturization of the system, the development of a dust-separation unit, and conducting space-qualification tests. A compact version could eventually be sent aboard a lander to an icy moon, bringing scientists closer to unlocking the mysteries hidden beneath extraterrestrial ice.

On Earth, the same technology could aid in avalanche prediction. Field tests in collaboration with the Austrian Research Centre for Forests showed the laser drill”s capability to measure snow density without the need for digging pits. When mounted on a drone, it could collect data from perilous slopes inaccessible to humans.

Whether applied on Earth or in distant space, the laser drill aims to penetrate surfaces and unveil the secrets concealed within ice.

The team”s findings were published in the journal Acta Astronautica on September 8.