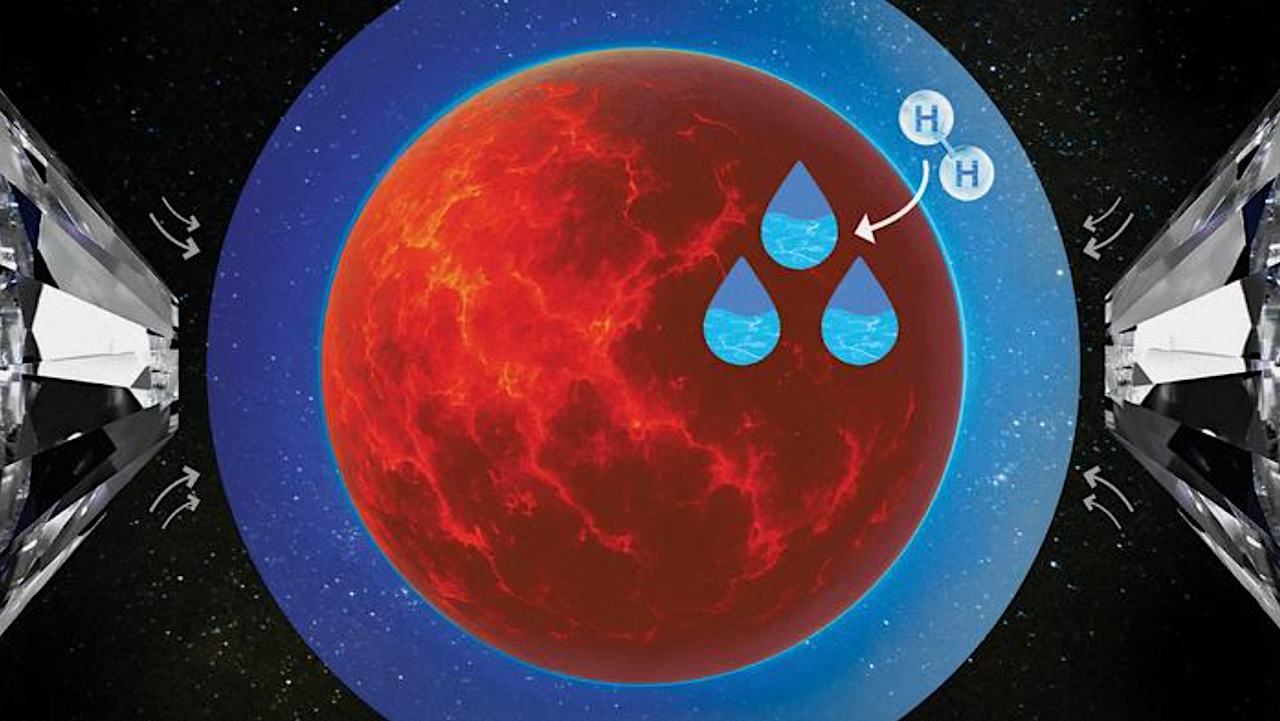

Recent research published in Nature by scientists from the Carnegie Institution, including Francesca Miozzi and Anat Shahar, suggests that the most common type of planet in our galaxy, known as Sub-Neptunes, may possess abundant liquid water. This water is thought to form through interactions between molten magma oceans and early atmospheres during the planets” formative stages.

Among the over 6,000 identified exoplanets in the Milky Way, Sub-Neptunes are smaller than Neptune and more massive than Earth. They likely feature rocky cores surrounded by thick atmospheres primarily composed of hydrogen. This unique composition makes them ideal candidates for exploring how rocky planets, including Earth, accumulated large amounts of water, which is essential for the emergence of life.

Miozzi noted, “Our rapidly increasing knowledge about the diversity of exoplanets has allowed us to rethink the early stages of rocky planet formation and evolution.” This research provides a fresh perspective on a long-standing enigma regarding the origin of water on planets. Previous experiments targeting this issue were notably lacking.

This investigation is part of the interdisciplinary AEThER (Atmospheric Empirical, Theoretical, and Experimental Research) project, spearheaded by Shahar and supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The project integrates diverse scientific fields such as astronomy, cosmochemistry, and mineral physics to address fundamental questions related to the conditions necessary for rocky planets to support life.

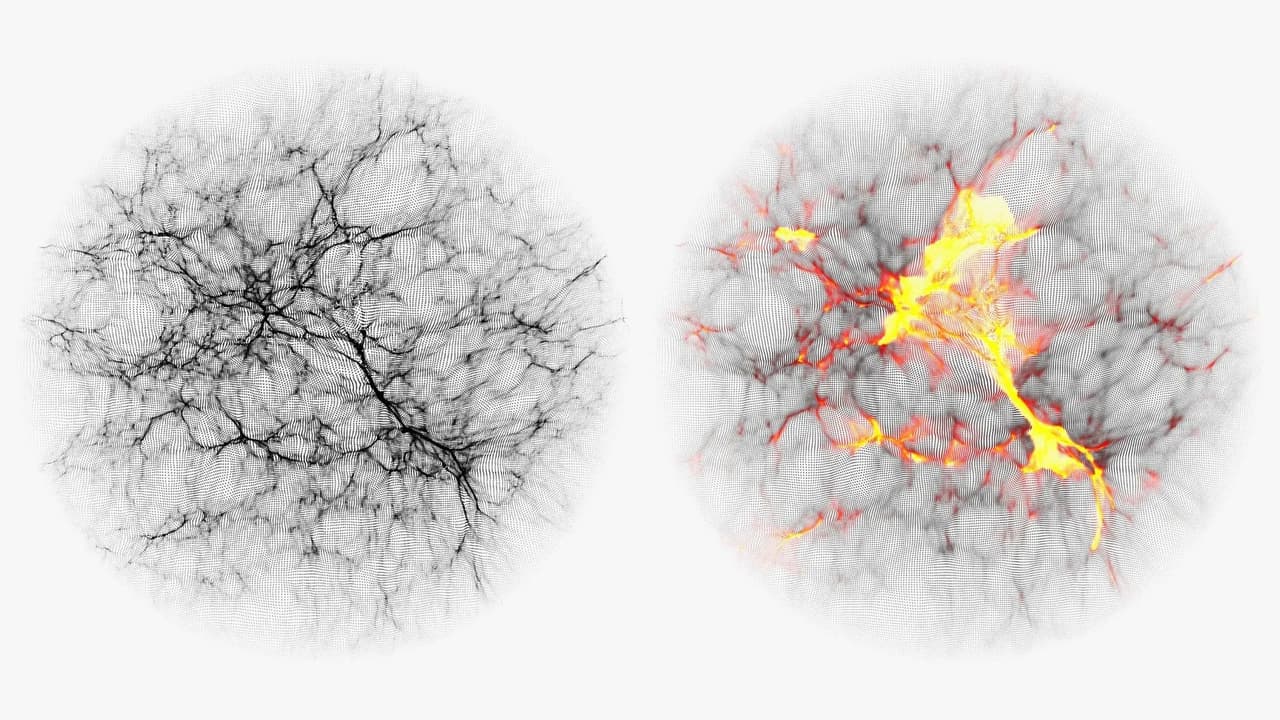

The research team conducted experiments that simulated the conditions of early planetary atmospheres and magma oceans. By compressing samples to nearly 600,000 times the atmospheric pressure and heating them to over 4,000 degrees Celsius, they recreated the environments present during the formative years of these celestial bodies.

These young planets form from a disk of gas and dust surrounding a new star. As material coalesces, it collides and grows, leading to intense heat and the formation of magma oceans. These bodies are often enveloped in thick hydrogen atmospheres that can insulate the magma for billions of years, delaying its cooling.

Miozzi stated, “Our findings provided the first experimental evidence of two crucial processes in early planetary evolution. We demonstrated that a substantial amount of hydrogen dissolves in the melt, leading to significant water production through the reduction of iron oxide by molecular hydrogen.”

The results indicate that large amounts of hydrogen can be retained in the magma ocean while water is being generated. This discovery has significant implications for understanding the physical and chemical characteristics of a planet”s interior, potentially influencing both core formation and atmospheric makeup.

Shahar concluded, “The presence of liquid water is vital for planetary habitability. Our work shows that substantial quantities of water are created as a natural outcome of planet formation, representing a major advancement in how we approach the search for extraterrestrial life.”