Researchers have made significant strides in understanding how compact neutron stars can become before collapsing into black holes. This new analysis offers a framework to potentially test the principles of quantum chromodynamics under extreme conditions.

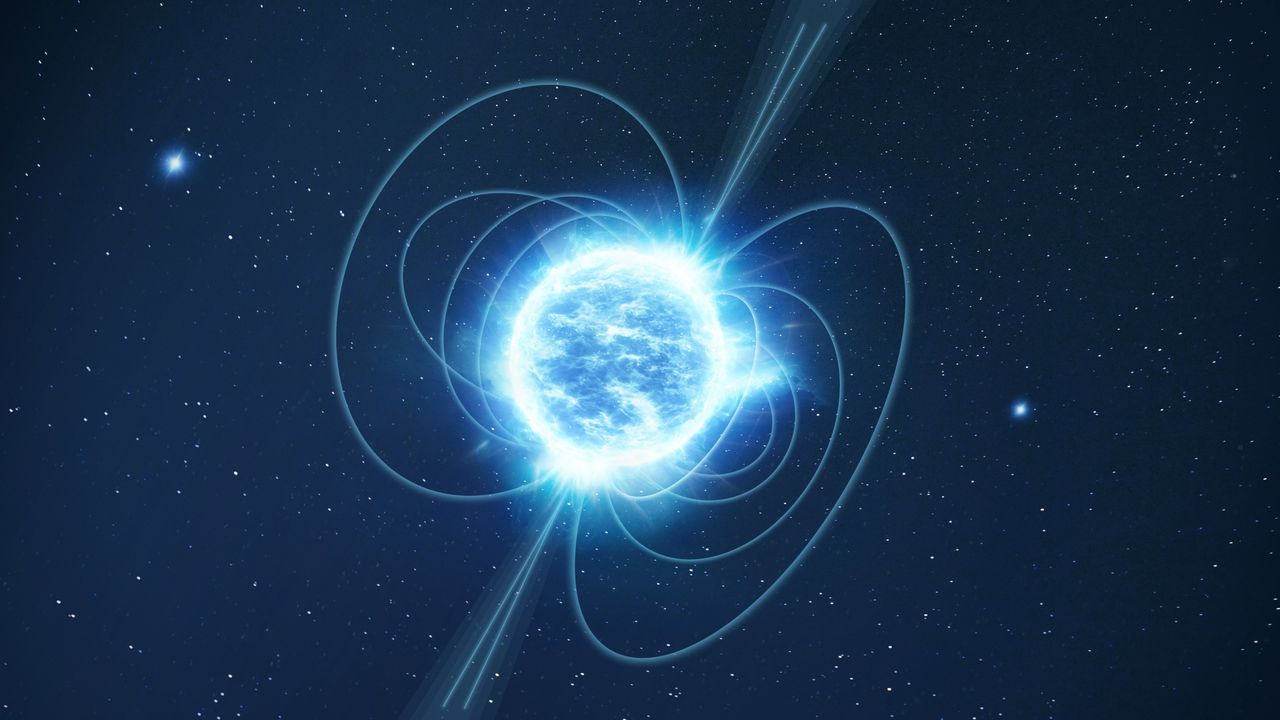

Neutron stars, the remnants of massive stars that have undergone supernova explosions, are incredibly dense objects, often containing up to three times the mass of the sun within a volume of approximately a dozen miles in diameter. Despite the ability to measure a neutron star”s mass with precision, determining its radius has proven to be a complex challenge, according to Luciano Rezzolla, a professor of theoretical astrophysics at the University of Frankfurt.

In collaboration with his colleague Christian Ecker, Rezzolla has conducted a study that clarifies some of the uncertainties surrounding neutron star compactness. The difficulty in measuring a neutron star”s radius stems from its great distance from Earth and the complexities of what physicists refer to as the equation of state. This equation describes the internal density and pressure of a neutron star, which are critical for deriving its radius and other properties.

The extreme conditions within neutron stars push our comprehension of nuclear physics to its limits. For instance, a mere spoonful of neutron star material can weigh billions of tons, resulting in the crushing of atoms and the merging of protons and electrons to form a neutron-dominated structure. In the heart of these stars, unusual physics may take over, potentially allowing for the existence of “strange” matter particles known as hyperons or even causing neutrons to behave in ways that allow their constituent quarks to move freely.

Currently, it is impossible to recreate the conditions present inside neutron stars in a laboratory setting on Earth, which complicates the study of their properties. Consequently, there exists a variety of equations of state, each corresponding to different models of neutron star conditions. To determine the limits of neutron star compactness, Rezzolla and Ecker analyzed tens of thousands of these equations.

They focused on the most massive neutron star scenario for each equation, noting that general relativity predicts a maximum mass limit for neutron stars. Observations suggest this limit lies between two and three solar masses. Surprisingly, the researchers discovered an upper limit on the compactness of neutron stars, indicating that the mass-to-radius ratio is always less than one-third. This crucial ratio, described using geometrized units common in general relativity, allows mass to be expressed in terms of length.

With an established upper limit on compactness, Rezzolla explained that it is now possible to infer a lower limit on a neutron star”s radius. Once the mass of a neutron star is known, its radius can be inferred to be greater than three times its mass. This ratio holds true across all equations of state, which is unexpected since one might assume that the most massive stars would also be the most compact due to their stronger gravity.

The relationship derived by Rezzolla and Ecker is rooted in principles of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the theory governing how the strong force binds quarks into particles like neutrons. If future observations reveal a neutron star with a compactness exceeding one-third, it would suggest flaws in the QCD assumptions employed in their analysis.

Future advancements in observing neutron stars may soon allow for precise radius measurements, providing an opportunity to test the relationship developed by the researchers. Rezzolla remains optimistic, citing the ongoing NICER experiment on the International Space Station and gravitational wave events, particularly the merger of black holes with neutron stars. The merger of two neutron stars, as seen in the event GW 170817, could yield tighter constraints on neutron star radii.

The findings of Rezzolla and Ecker have been published as a pre-print paper on arXiv.