Recent simulations indicate that the early universe played a significant role in the growth of black holes, although this accelerated growth may not persist over time. Located approximately 27,000 light-years from Earth, the Milky Way harbors a supermassive black hole with a mass exceeding 4 million suns. Most galaxies are believed to contain such black holes, with some, like the one in the elliptical galaxy M87, weighing around 6.5 billion suns. The largest known black holes can exceed 40 billion solar masses. Despite their prevalence, the mechanisms behind their formation remain a subject of intense study.

One prevailing theory suggests that supermassive black holes develop gradually through a series of mergers. Galaxies, influenced by dark matter and dark energy, form in clusters separated by vast voids. Over time, these voids expand while galaxies come together, eventually resulting in mergers. Consequently, the black holes situated within these galaxies also combine to form the massive entities observed today. If this model holds true, then the most distant galaxies should harbor smaller black holes, in the range of millions of solar masses, with billion-solar-mass counterparts appearing only in the more proximate universe.

However, observations from the James Webb Space Telescope have revealed that numerous distant galaxies contain supermassive black holes that are already enormous, some exceeding a billion solar masses, when the universe was merely half a billion years old. These early giants cannot be adequately explained by the merger model and challenge established theories of black hole formation.

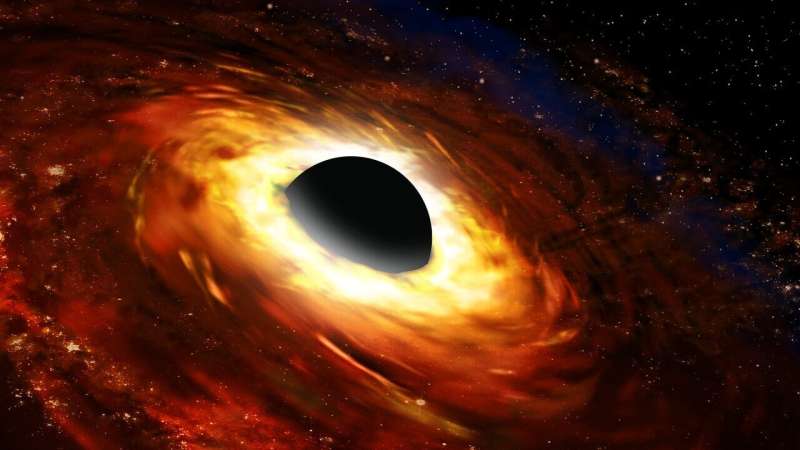

The question arises: why couldn”t black holes in the dense early universe grow rapidly with abundant matter available? The answer lies in what is known as the Eddington Limit. As matter spirals toward a black hole, it transforms into an extremely hot, high-pressure plasma, which in turn repels additional matter from the vicinity, thus slowing the growth rate. The Eddington Limit defines the maximum pace at which a black hole can grow, and current understanding suggests that this rate is insufficient to explain the presence of the massive black holes observed in the early universe.

Interestingly, the conditions of the universe during its infancy are believed to differ markedly from those today. A recent study published on the arXiv preprint server addresses this possibility. The authors utilized advanced hydrodynamic models to investigate black hole formation during the cosmic dark age, a period characterized by the cooling of electrons and nuclei into atoms, preceding the reionization that heralded the creation of the first stars.

The findings indicate that there was a brief period of super-Eddington growth, where regions of sufficiently high density prevented the surrounding hot material from dispersing. This phenomenon allowed early black holes to expand at rates unattainable in the current universe, but only up to about 10,000 solar masses. Beyond this threshold, the Eddington feedback mechanism reasserts itself, curbing further growth.

Moreover, the research suggests that this super-Eddington phase does not significantly enhance long-term black hole growth. Ultimately, even black holes that consistently grow at a pace below the Eddington Limit will converge to similar mass levels over time. This study implies that super-Eddington growth cannot fully account for the billion-solar-mass black holes observed in the early universe. Given that galactic mergers also fail to provide a satisfactory explanation, the findings point toward an alternative hypothesis: the existence of seed mass black holes that may have formed very early, possibly during the inflationary epoch immediately following the Big Bang.

For further details, refer to the work by Ziyong Wu and colleagues titled “How Fast Could Supermassive Black Holes Grow At the Epoch of Reionization?” available on arXiv.