Recent research published in The Astrophysical Journal investigates the capacity of water-rich exoplanets to survive in close orbits around white dwarf stars, which are the remnants of Sun-like stars. The study aims to determine if these small, rocky planets could potentially support life.

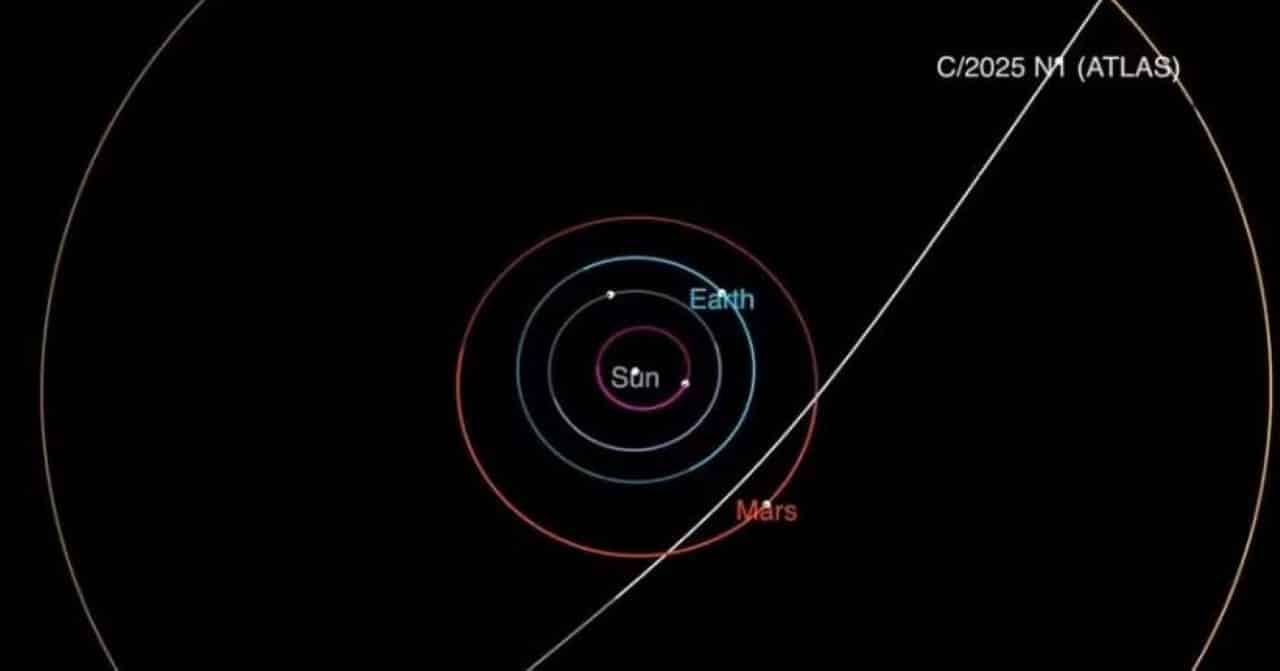

The research team utilized mathematical models to evaluate how first-generation exoplanets, which formed alongside their host stars, can retain water as they migrate inward toward a white dwarf during the star”s evolution from a Sun-like star to a white dwarf.

Initially, the researchers calculated the effective temperature of these planets to define their habitable zones, noting that this zone shifts as the star transitions through its lifecycle. They also analyzed the amount of water that could evaporate from a planet”s surface due to increased solar radiation and assessed the impact of planetary scattering events, which occur when planets pass closely enough to influence each other”s orbits.

The findings indicate that Earth-sized or Mars-sized planets would require significantly larger initial water reserves than Earth possesses or need to originate from much farther out than their final positions. The study highlights that the intense radiation experienced by planets in close proximity to white dwarfs could lead to complete evaporation of their water.

In their conclusions, the researchers stated, “We found that planets starting with large initial reservoirs of water and located at considerable distances from their host stars are more likely to retain their oceans. Moreover, the timing of planetary migration and the onset of tidal heating plays a crucial role in determining the fate of these water reserves. If a scattering event that initiates planetary migration occurs after the white dwarf has sufficiently cooled, the feasibility of ocean retention increases due to reduced XUV radiation.”

White dwarfs form after a Sun-like star exhausts its nuclear fuel and undergoes a transition into a red giant phase, shedding its outer layers. The final stage results in a white dwarf that is roughly the size of Earth but contains around 60 percent of the original star”s mass, making it incredibly dense—about the weight of several tons per teaspoon.

While our Sun is currently about 4.6 billion years old, it is expected to remain in its main sequence phase for an additional 5 to 7 billion years before transitioning to a white dwarf.

This study contributes to the ongoing efforts of astronomers to locate habitable worlds and the potential for life. Traditionally, the search has focused on Sun-like stars, but this research suggests that white dwarfs could also be promising candidates for astrobiological studies. Future investigations may delve deeper into the possibilities of water retention on Earth-like planets orbiting these stars.

What new discoveries about the habitability of exoplanets around white dwarfs will emerge in the years to come? Only time will reveal these answers.

Laurence Tognetti, a six-year USAF veteran, brings extensive experience in journalism and science communication, specializing in space and astronomy.