The Institute for Data-Intensive Engineering and Science (IDIES) held its annual symposium on October 16. The event commenced with an address from Alex Szalay, the Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Big Data and Director of IDIES, who discussed the swift progression of data science and its growing range of applications.

Over the past quarter-century, numerous scientific advancements have been made possible through distinctive data sets, including the comprehensive mapping of the human genome via the Human Genome Project and the astronomical observations conducted by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS). “We are living through a revolution with an unprecedented pace and agility,” Szalay stated, underscoring that “half of the material we teach in semester-long courses will be either incorrect or outdated by the semester”s end.”

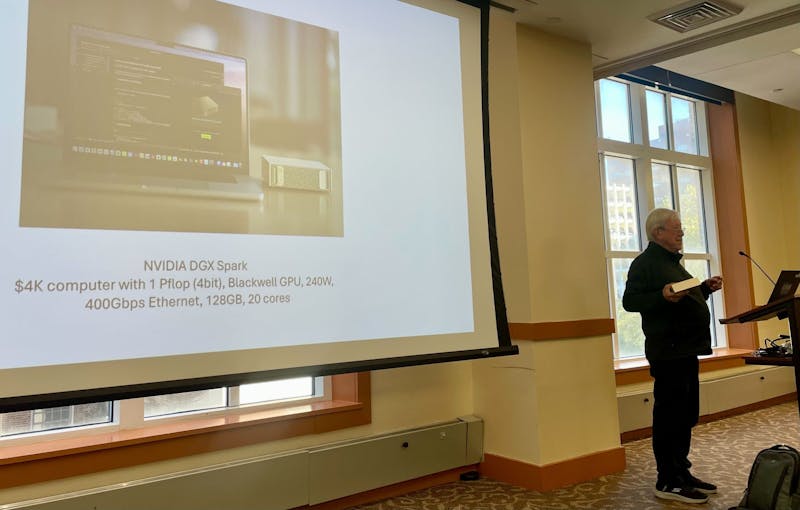

To illustrate the remarkable strides in computing technology, Szalay introduced the newly launched NVIDIA DGX Spark. This lightweight device, weighing only 2.65 pounds and approximately the size of a book, features 128 gigabytes of coherent unified system memory, allowing both the CPU and GPU to access the same data without unnecessary transfers. This power enables it to operate large language models such as OpenAI”s GPT-OSS 120B and Meta”s Llama 3.1 70B. A decade ago, such advanced computing was limited to engineers engaged in well-funded projects; now, a $4,000 credit card purchase suffices for anyone to access this technology.

“I predict that each of these machines will be capable of running a generative AI alongside every microscope in the lab and filtering data from every telescope,” Szalay noted, highlighting the deepening connections between artificial intelligence, data science, and broader research initiatives. While high-performance computing is undeniably becoming more accessible globally through the internet and open-source platforms, Szalay pointed out that various factors still result in unequal access to computing resources and their advantages. He concluded his remarks by stating, “The future is already here. It”s just not evenly distributed.”

Following Szalay”s introduction, keynote speaker Stuart Feldman, Chief Science Officer and President at Schmidt Sciences, delivered a presentation titled “Scientific Software, Software Engineering, and Philanthropy.” He acknowledged that while we possess tools to generate and gather vast amounts of data at unprecedented speeds, interpreting this data into comprehensible and actionable insights remains a significant hurdle. Feldman stressed the critical role of software innovation in overcoming this challenge.

“Scientific computing is our sole means of understanding complex phenomena,” Feldman explained. He noted that while mathematics has provided valuable techniques for linear equations, real-world complexities often defy linearity, necessitating robust engineering solutions. He referenced his own software, Make, which he developed nearly 50 years ago and continues to be utilized in Unix operating systems today.

Scientific software has greatly facilitated the analysis of extensive datasets, the simulation of intricate systems, and the automation of repetitive tasks, all of which are crucial for contemporary research across various fields, including astrophysics, genomics, biological sciences, climate studies, and materials design. During the symposium, faculty and students showcased projects that were data- and computation-intensive, including a real-time model of the stomach that combines fluid dynamics with AI software.

Feldman highlighted the enduring significance of well-developed software, remarking, “Software for science is a genuine blend of mathematics, feedback loops, statistics, and real-time data. It must be accurate.” He recounted a personal experience illustrating the disparity between part-time graduate students and full-time professional engineers working on research projects, noting the stark contrasts in quality. “A basic rule is that a graduate student has only one job: to exit with one piece of paper in and one piece of paper out, whereas well-crafted code may endure for decades.”

Despite concerns that the rapid rise of AI might make some jobs obsolete, Feldman emphasized the need for the intuition, adaptability, and experience of skilled engineers and problem-solvers, which are essential for maintaining scientific integrity. He elaborated, “On one side, there”s software engineering for AI, which involves building large model systems. This is intensive, scientific computing. Even with delicate correction factors in play, the scale is unprecedented, necessitating a rigorous engineering discipline for validating computations. Only we can verify the results.”

While AI undoubtedly offers significant conveniences across various tasks, Feldman cautioned against over-reliance on it. “To what extent can AI perform tasks for you? To what extent do you trust its accuracy? Why should it not be hallucinating your test results as well?” He humorously added that “no AI system will I trust more than an experienced plumber.”

In conclusion, Feldman articulated a crucial point: “This is the mass implication. How do we ensure software is developed correctly? How do we create credible and timely answers?” The responsibility lies with us, as future scientific breakthroughs will depend not merely on faster computers, but on the wisdom and expertise of those who know how to utilize these tools effectively.