Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology have created a novel adaptive lens inspired by the human eye, which could provide vision capabilities for soft robots. This innovative device, known as the photo-responsive hydrogel soft lens (PHySL), is made from flexible, light-sensitive materials that mimic the properties of biological tissues.

Typically, adjustable camera systems rely on solid, heavy lenses and moving parts to manage focus and light intensity. However, human eyes achieve these adjustments through soft, pliable tissues, allowing for a compact design. The PHySL lens replaces traditional rigid components with soft polymers that function as artificial muscles. These polymers are derived from a hydrogel, a water-based material that alters the shape of the lens to change its focal length, similar to the action of ciliary muscles in human eyes.

The hydrogel responds to light by contracting, enabling remote control of the lens simply by projecting light onto its surface. This capability allows for precise manipulation of the lens shape by selectively illuminating different sections of the hydrogel. By eliminating rigid structures, the system enhances flexibility and durability, making it safer for use in conjunction with the human body.

The significance of this development extends beyond mere vision. Current artificial vision technologies predominantly rely on rigid optics powered by electricity, posing challenges for soft robotics and biomedical devices that require low-power, flexible materials. The soft lens design aligns perfectly with the needs of these emerging fields, which seek to integrate adaptable and compliant structures.

Soft robots, inspired by the flexibility of animals, are constructed from materials that allow them to adapt to various environments. This flexibility enhances their durability and functionality. The newly developed lens technology is being explored for various applications, including surgical endoscopes, delicate object handling grippers, and robots that can navigate challenging terrains where traditional rigid robots struggle.

In the biomedical sector, the lens could improve the interface between machines and the human body, making devices safer and more effective. Applications may include skin-like wearable sensors and hydrogel-coated implants, which can move in harmony with the body.

This research also represents a convergence of tunable optics and soft “smart” materials. Despite their potential, many previous designs for soft lenses faced challenges due to reliance on liquid-filled compartments or electronic components, which complicated their integration into delicate or untethered systems. The light-activated design offers a streamlined alternative that avoids these issues.

Looking ahead, the research team aims to enhance the performance of the soft lens by utilizing advanced hydrogel materials. Recent studies have introduced hydrogels that respond more quickly and powerfully to stimuli. The objective is to integrate these advancements to bolster the capabilities of the PHySL lens.

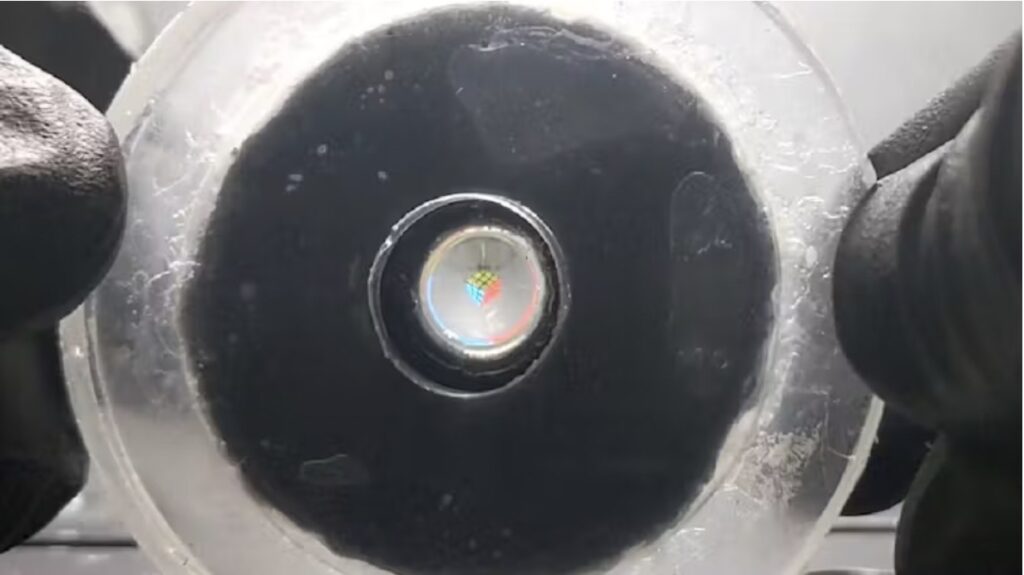

Currently, a proof-of-concept camera has been developed that operates without electronics, utilizing the soft lens and a custom light-activated microfluidic chip. Future plans include embedding this system within a soft robot, providing it with vision capabilities that do not rely on conventional electronics. This initiative could showcase the transformative potential of this innovative design for soft visual sensing.

This research is conducted by Corey Zheng, a PhD student in biomedical engineering, and Shu Jia, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.